Massive turnout, voters of color — new data fill in the details on Biden’s election win

David Lauter | May 10, 2021

High turnout among voters of color, increased support among white voters with college degrees, and a stop — or a least a pause — in declining support for Democrats among white voters without degrees: President Biden needed all of that for his victory in November and he, or some other Democrat, will probably need those factors to align again in 2024.

The release of census data on who voted last year, as well as a new analysis of the results from a leading Democratic data firm, has filled in many of the details of Biden’s victory, providing numbers to fuel the continuing debate within the party about who deserves the most credit for the win and what policies would make a repeat most likely.

The most striking feature of the election remains the outsize turnout — the largest as a share of the eligible population since the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in 1920 roughly doubled the size of the potential electorate by giving voting rights to women.

“Turnout rates went up for everyone,” said Michael McDonald of the University of Florida, the nation’s leading expert on the topic.

The higher numbers across the board meant that even groups that shrank as a share of the electorate still produced more votes. So, for example, more white Americans voted than ever before, even though whites declined as a share of the electorate, continuing a trend that has seen the voting population grow steadily more diverse over the last couple of decades.

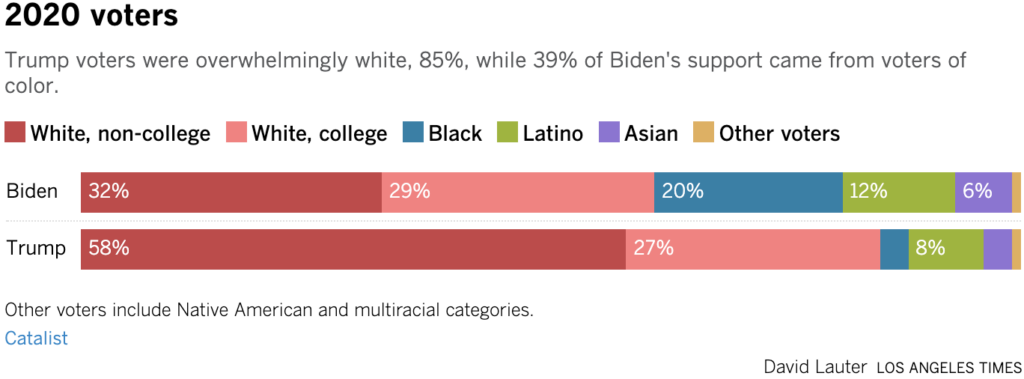

Biden benefited from that growing diversity. Roughly 4 in 10 of his votes came from people of color, according to a newly released analysis from Catalist, the Democratic data firm. President Trump’s voters, by contrast, were overwhelmingly white, 85%, according to the firm’s estimates, with just 15% coming from people of color, mostly Latinos.

Biden also gained from increased support for Democrats among white voters with college educations.

Those voters, many of whom live in suburban areas, swung sharply against Trump in the 2018 midterm election and stuck with Biden in 2020, said Yair Ghitza, Catalist’s chief scientist. “In the Trump era, white college voters have become an increasingly core piece of the Democratic coalition,” Ghitza said. A big question for the next couple of elections is, “will that continue?”

Biden didn’t improve among whites without a college degree — Trump’s core group — but he didn’t lose any further ground among a group that remains a majority of voters in many key states.

Exactly how well a candidate did among different population groups can never be known for sure because ballots are secret. On election night, exit polls try to estimate the breakdown by surveying voters and asking which candidate they favored. Exit poll estimates, although often cited, are highly imperfect.

In the months since the election, additional numbers become available that improve those estimates. The census conducts a survey that asks Americans whether they voted — although not for whom. And firms like Catalist glean data from state voter files, which are public, to determine who voted. They then apply complex models of the electorate that they’ve honed over several election cycles to analyze racial, ethnic and other breakdowns.

For political parties, two numbers are key to analyzing how the vote changes from one election to the next: What share of the electorate does each population group make up, and how did the party’s level of support change from each group?

In 2020, Latino and Asian voters increased as a share of the electorate, while the white share declined. The share cast by Black voters remained steady.

Turnout among Latino voters was up 31% compared with 2016, and Asian turnout increased 39%, according to Catalist’s estimates. As a result, the Latino share of the 2020 electorate expanded from 9% to 10%; Asian voters made up about 4% of the total.

Turnout among Black voters, which was already high, increased by 14%. That’s just slightly more than the rate by which the overall electorate grew, which meant Black voters remained at 12% of the total.

White voters remain by far the largest racial group in the electorate, but their share fell to 72% from 74% in 2016 and 77% in 2008, when President Obama won his first term.

Much of the drop among white voters came from those without college degrees. Because the popularity of college has grown a lot in recent decades, the non-college-educated population skews older, especially among white Americans. In 2008, non-college-educated white voters made up just over half the electorate, but by 2020, they had declined to just over 4 in 10.

In 2016, Trump was able to eke out a victory by boosting the Republican share of those non-college white voters. In 2020, with their ranks continuing to shrink relative to the overall population, he was able to stay in contention by improving his vote share among Latinos and, to a lesser extent, among Black voters — a result that startled many Democrats.

Latinos went from 71% support for Hillary Clinton in 2016 to 63% for Biden in 2020.

“That’s no small move,” said Democratic analyst Ruy Teixeira, who sees it as a worrying portent.

The drop varied significantly from state to state, the Catalist analysis notes, with Latino support for the Democratic ticket falling 14 percentage points in Florida compared with 2016 and 9 points in Texas, but only 4 points in Georgia and 5 in Arizona, which Biden won.

Black voters, by contrast, continued to support the Democrats overwhelmingly. The 90% of the Black vote that went to Biden was slightly lower than the 93% Clinton received, but that was more than made up for by higher Black turnout, Catalist estimates.

The trends toward a more educated and more racially diverse electorate will continue for years, posing a challenge for Republicans nationally, McDonald said.

“No wall can be erected to stop that,” he said. Laws that many Republican-majority states have begun to pass that make voting more difficult are “a rear-guard action trying to eke out a few more election cycles” from the older, whiter electorates of the past, he said.

“It’s like putting your finger in the dike. It’s not going to stop the rising water.”