By Yair Ghitza and Jonathan Robinson

Interactive Data Visualizations by Chase Stolworthy, Edited by Aaron Huertas, Site design by Melissa Amarawardana

The 2020 election was historic and uniquely challenging. Not only was it conducted in the middle of a global pandemic, but it was one of the most intensely partisan elections in recent history. Despite these immense challenges, America’s democratic process survived. Election administrators, poll workers and voters themselves rallied to deliver the highest voter turnout in over a century, higher than any election since women’s suffrage or the Voting Rights Act. Democrats Joe Biden and Kamala Harris defeated Donald Trump and Mike Pence in an election that was closer than many analysts expected, and many down-ballot races were even closer.

We'd like to thank our partners whose insights and contributions have been invaluable in making sense of the 2020 election. Further, this report would not have been possible without the dedication of many on the Catalist team, whose hard work maintaining this national database is paramount to our ability to produce this report.1We would like to particularly thank Meg Schwenzfeier, Molly Norton, Justine D'Elia-Kueper, Maggie Dart-Padover, Peter Casey, Sarah Grant, Alan Julson, Anna Thorson, Jesse Zlotoff, Andres Cremisini, Hersh Gupta, Matt Zetkulic, Anna Baringer, Russ Rampersad, Dan Buttrey, Marguerita ten Houten, Jordan Tessler, Mary Toole, John Kim, Erin Thomas, and Nicholas Petrone in particular for their many important contributions to this project.

What Happened in 2020

Topline Takeaways

Based on our analysis to date, the following are our 10 big takeaways for election results for the top-of-the-ticket presidential race. We’ll return to the Senate, House and other down-ballot elections in future reports in this series.

But before we dig in, we want to emphasize that no one has perfect, certain knowledge about the electorate. The fact that someone has voted is a matter of public record, but how we vote is private. Therefore, these data points are all estimates, based at least partly on survey data and statistical modeling. In our own work, we compare our results to other data sources, and we encourage readers to do the same.

This was the most diverse electorate ever.

The voting electorate continues to become more diverse, and 2020 was the most racially diverse electorate ever. This was due to big turnout increases in communities of color, particularly among Latino and Asian voters. The electorate was 72% white, compared to 74% white in 2016 and 77% white in 2008. This composition shift comes mostly from the decline of white voters without a college degree, who have dropped from 51% of the electorate in 2008 to 44% in 2020.

Biden and Harris won with a multiracial coalition.

The Biden-Harris ticket benefitted from a diverse set of supporters: 39% of their coalition were voters of color, and the remaining 61% were split fairly evenly between white voters with and without a college degree. They also made significant gains among white voters compared to 2016, particularly among white college and white suburban voters, who have shown a solid and consistent backlash against Trump’s Republican party. The Trump-Pence ticket was more homogenous, with nearly 60% of their votes coming from white non-college voters, 85% white in total, and only 15% voters of color.

Latino voters continued to favor Democrats, but Republicans made inroads with Latino voters, too.

Along with massive increases in turnout, Latino vote share as a whole swung towards Trump by 8 points in two-way vote share compared to 2016, though Biden-Harris still enjoyed solid majority (61%) support among this group. Some of the shift from 2016 appears to be a result of changing voting preferences among people who voted in both elections, and some may come from new voters who were more evenly split in their vote choice than previous Latino voters. This question presents particularly challenging data analysis problems, which we discuss more in a dedicated section below.

Black voter turnout increased substantially, resulting in significant gains for Democrats, despite a modest overall drop in Democratic support levels.

Black voter turnout increased substantially, while overall Black vote share swung towards Trump by 3 percentage points compared to 2016. This dynamic – many more voters turning out but at a slightly lower Democratic margin – resulted in more net Democratic votes from Black voters in 2020 than in 2016, particularly in several key battleground states. For both Black and Latino voters, we discuss how an expanding electorate might bring marginal voters into the electorate at slightly lower support levels.

Asian-American and Pacific Islander voters saw the largest relative increase in turnout, which benefited Democrats.

Even in a high turnout year, AAPI voters had a remarkable jump in turnout, the biggest increase among all groups by race. The number of AAPI voters increased 39% from 2016, reaching 62% overall turnout for this group. AAPI voters remain strongly supportive of Democrats, delivering a 67% vote share to the Biden-Harris ticket, largely consistent with past elections.

The urban-rural voting divide continues to be immensely important, with suburbs growing more Democratic and more racially diverse.

The relationship between urbanity and voting is essentially as strong as ever, though it did not grow wider in 2020 than in recent years. Rural areas continued to vote strongly for Trump, while Biden continued to enjoy dominant support levels in cities. There were slight changes in both, however, as Biden’s vote share increased by 1 percentage point in rural areas and dropped by 3 points in urban areas. The Biden-Harris ticket maintained gains in the suburbs that began earlier in the Trump presidency. These gains are not all about white suburban voters, as is sometimes misunderstood. Suburbs are increasingly racially diverse, which accounts for part of the change in voting patterns.

Women remain critical to the Democratic coalition.

Women comprise 54% of the electorate overall and an even larger majority of the electorate among Black (59%) and Latino (56%) voters. Overall, women voters of color supported the Democratic ticket at a rate of 79% while support among white women was 48%. We find a 10-point gender gap, with women supporting Democrats more than men fairly consistently across races. White college-educated women in particular have shifted against Trump, moving from 50% Democratic support in 2012 to 58% in 2020, a trend that began in 2016 and continued in 2018 and 2020.

Young voters drove record-breaking turnout.

2020’s historic voter turnout gains were primarily driven by young voters. 18-29 year olds grew from 15% (2016) to 16% (2020) of the voting electorate, but the generational changes have been even more dramatic. Millennials and Gen Z now account for 31% of voters, up from 23% in 2016 and 14% in 2008. Meanwhile, Baby Boomers and older generations have been gradually shrinking, from 61% of the electorate in 2008 to 44% in 2020.2We use the Pew Research Center’s definition of generations. People in Gen Z were born in 1997 or later; Millennials 1981-1996; Gen X 1965-1980; Baby Boomers 1946-1964; Silent Generation 1928-1945; Greatest Generation 1927 or earlier.

New voters made a big difference, especially in Sunbelt swing states.

We saw large numbers of new voters across the country. Nationally, 14% of voters were first-time voters, who we haven’t seen vote in a previous even-year general election. This understates the change from 2016, however, due to many first-time 2018 voters and other sources of year-to-year turnover. When we compare state-by-state electorates from 2016 to 2020, 29% of voters were new presidential voters in their state in 2020. Some of these voters registered and voted for the first time in 2018, others were brand-new in 2020 or moved from out of state. Turnover was especially large in Sunbelt battleground states.

There are still millions of non-voters who could cast ballots in future elections.

Electorates are dynamic, and millions of voters drop out and join the electorate with each midterm and presidential election. 2020 saw millions of first-time voters, even though campaigns and civic engagement organizations were not able to run traditional registration, canvassing or get-out-the-vote operations due to the pandemic. At the same time, over 70 million eligible citizens did not cast a vote in 2020 and may cast ballots in the future, further changing the electoral landscape.

In-Depth Analysis

Voter Turnout and Composition of the Electorate, by Race

Perhaps the most salient aspect of the 2020 election was the historic level of voter turnout. Turnout went from 139 million votes in 2016, to a record high of 160 million votes in 2020, a 12% increase overall.

While some of this was driven by population growth, the vast majority of the increase was simply due to increased voter enthusiasm and, perhaps, easier access to the polls.3It is certainly true that higher voter turnout coincided with easier access to the polls, but we are aware of the difficulties in assigning causal relationships here and do not want to imply otherwise. On the former point, Michael McDonald from the University of Florida’s United States Election Project projects that voter turnout grew from 60% to 67%, as a percent of the eligible voting population. This 2020 number is the highest in his dataset since 1900 – exceeding even the artificially high turnout of elections held before women’s suffrage and the Voting Rights Act – and follows a historic rise in voter turnout in the 2018 midterm elections two years ago.

Figure 1: Increase in Number of Votes by Race, 2016-2020

This overall turnout growth is astounding, but turnout grew differently across different demographic groups. Figure 1 above shows the growth in terms of number of votes from 2016 by race. Turnout growth was highest among AAPI voters (+39% compared to 2016) and Latino voters (+31%), and it was higher than average for all communities of color. White voters with a college degree (+13%) grew more than white voters without a college degree (+11%). These trends are partially driven by differential population growth, and some of the differences are more muted when examining turnout rate, which accounts for population growth.4This is an important point that we plan to examine in greater depth along with recents updates to the U.S. Census. Regardless, we expect the remarkable increase in AAPI turnout to continue to stand out across different metrics.

Regardless, it is important to note that even if population growth does occur, it doesn’t necessarily imply that voter turnout will follow suit. In other words, it is important that these growing populations are not simply staying on the sidelines, but are able to register and vote at higher numbers, too.

Figure 2: Composition of the Electorate by Race, 2008-2020

| Race | 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | 2016 to 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 77% | 76% | 74% | 72% | -2.0% |

| Black | 12% | 13% | 12% | 12% | -0.1% |

| Latino | 7% | 7% | 9% | 10% | +1.2% |

| AAPI | 3% | 3% | 4% | 4% | +0.8% |

| Other | 1% | 1% | 2% | 2% | +0.1% |

| White Non-College | 51% | 48% | 46% | 44% | -1.6% |

| White College | 26% | 27% | 28% | 28% | -0.4% |

These changes resulted in the most racially diverse electorate on record. We estimate that 72% of the electorate was white, down 2 percentage points from 2016. This comes almost entirely from the decline in white voters without a college degree, who continue a steady decline (in percentage terms) over our entire dataset, and indeed even longer than that. As recently as 2008, white non-college voters were a (bare) majority of the electorate. While they remain the largest plurality voting bloc in the country, they are down to 44% of the electorate in 2020.5Data sources disagree on various estimates, but we and others have noted a particular emphasis on this number: the size of the white non-college voting electorate. The most commonly cited data sources show the following numbers: Catalist: 44%, Cooperative Election Study: 44%; VoteCast: 43%; Current Population Survey: 40%; Exit Poll: 35%. The most notable difference comes from the CPS, which was released very close to our own deadline for publishing this report. The differences between CPS and Catalist here are a function of differences on race (which are expected, more below), and differences on college education level. Looking at past elections, the CPS is normally about 2 percentage points more college-educated than our model. Their 2020 numbers diverge more than that, showing college graduates as 41% of the electorate, compared to 37% in our data. Similarly, they show a 2 point increase from 2016 to 2020, while we show a 0.6 point increase (which is difficult to see in our crosstabs due to rounding). Fully analyzing the differences between CPS and Catalist is beyond the scope of the report, but our intuition is that it is likely a result of some combination of (a) increasing missing value problems in the CPS due to the pandemic, and (b) our college-educated growth projections are probably a little too conservative. Seeing the CPS data, we think the college-educated percent is likely a point higher than what we are reporting here.

Turnout Rates among the Citizen Voting Aged Population (CVAP)6For this graphic, we projected the citizen voting-aged population by race to 2020, using census data from the American Community Survey (ACS). It is difficult to compare census and voter file data at times, due to differences in how races are defined in surveys. The Census Bureau usually defines Hispanics as anybody of Hispanic descent. Our voter file models use different sources of data, sometimes including “single race” questions that do not include a separate question regarding Hispanic descent. This can lead to smaller estimates of the Hispanic population, mainly due to people who do not select the Hispanic option when they have to choose between Hispanic and White. There is similar definitional ambiguity for “Other” races, for instance regarding how multiracial respondents are coded. As a result, we consider these two numbers to have wide uncertainty bars around them. For comparison, the CPS reports a 54% turnout rate for Hispanics in 2020, a number that some academics have argued is too high. They do not publish an official estimate for “Other” races.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Despite historic voter turnout, roughly one out of three voting-age citizens did not vote in 2020, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. This shows that there are still major gains to be made in voter turnout writ large. This is particularly true among communities of color, where non-voting rates are substantially higher. Though there were major strides on this front in the 2020 election, longstanding disparities in racial and ethnic voting remain deeply entrenched. This is true nationally, and more so in particular areas of the country. For example, the data above includes the estimated number of voters and non-voters across battleground states in the South and West – Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, and Texas. Across these states, there are nearly as many non-voting people of color (11 million) as there are voters of color (13 million), mostly concentrated in Latino communities. The numbers look quite different among white people in these states, with only 9 million non-voters and 24 million voters.7Needless to say, the dynamics are different in other parts of the country.

Vote Choice

Historic voter turnout was perhaps the most eye-popping characteristic of this election, but different voters shifted their partisan vote preferences in meaningful ways, resulting in changes in the demographic makeup of the electorate as well as the partisan breakdown of distinct demographic groups.

In this section, we will examine the partisan voting preferences of different groups in the electorate. Throughout this section, we will primarily use two-way vote share for the Democratic candidate, i.e., what percent of the Democrat or Republican vote that (s)he received. This is different than reporting on vote margin, which is the difference between each party’s vote share.

Overall, in 2020 Biden received 52.3% of the (two-way) vote, compared to 51.1% for Clinton in 2016. This +1 shift looks fairly small, but it masks important demographic and geographic differences under the hood.

Figure 5 shows these changes by race, again emphasizing the difference between white non-college and white college voters. In 2020, we estimate that 44% of white voters supported Biden, up from 41% in 2016. Most of this was driven by gains he made among white college voters, as explored in more detail below. On the other hand, while support levels among voters of color remained high, they dropped overall, with the biggest drops coming among Latino voters. While these election-to-election changes are important, it is critical to remember that the levels of support for Biden remain substantially higher than other groups – 90% support among Black voters, 63% support among Latinos, 67% support among Asians, and 55% among Other races.

Vote Margin vs. Vote Choice

Different political analysts use one or the other, and when people talk in shorthand it is often unclear which one is being discussed. To be clear:

- In 2016, the final national popular vote was 48.2% for Clinton (D), 46.1% for Trump (R), and 5.7% third party. This corresponds to a 51.1% two-way vote share for the Democratic candidate – 48.2 / (48.2 + 46.1), and a +2.1% margin for Clinton.

- Analogous numbers for 2020 are 51.3% for Biden (D), 46.9% for Trump (R), and 1.8% third party, corresponding to a 52.3% two-way vote share and a +4.4% margin.

We prefer talking in two-way instead of margin, primarily because it makes differences easier to understand. For example, imagine some group of voters, moving from 55D-45R one election, to 60D-40R the next. In “two-way” terms, they moved from 55% to 60%, i.e, 5% of people changed their minds. In “margin” terms, they moved from +10 to +20, a 10 point shift. To a casual observer, this looks like twice as big of a change, causing confusion and inappropriately amplifying small changes to seem twice as large. This is an even bigger problem when we are dealing with uncertain survey-based estimates from one year to the next.

Figure 5: Two-Way (Democrat vs. Republican) Support for Democratic candidates, 2012-2020

| Race | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | 2016 to 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 42% | 41% | 44% | +3% |

| Black | 97% | 93% | 90% | -3% |

| Latino | 70% | 71% | 63% | -8% |

| AAPI | 66% | 68% | 67% | -1% |

| Other | 55% | 53% | 55% | +2% |

| White Non-College | 40% | 36% | 37% | +1% |

| White College | 46% | 50% | 54% | +4% |

Figure 6: Racial Composition of Biden and Trump Coalitions

Looking at composition and vote choice separately makes it somewhat difficult to see how the two interact, so Figure 6 combines them explicitly to show the racial (and educational) makeup of Biden and Trump’s coalitions. Despite modest drops in support levels among some voters of color, it is clear that Biden has a multiracial coalition, with 39% of his votes coming from Black, Latino, Asian, or Other races. Biden’s white voters were evenly distributed between those with or without a college degree, with nearly half of his white vote coming from each group. Trump’s coalition, on the other hand, was predominantly white, with 85% of his votes coming from white voters. About two-thirds of those white voters are people without a college degree (58% of his total). This continues a long-running trend over our entire dataset, where national-level Democratic coalitions are consistently more diverse than Republican ones.

White voters remained a super-majority of the electorate, but with significant divisions among the white voting bloc that bear scrutiny.

Figure 7: Democratic Vote Share of Selected Groups of White Voters, 2012-2020

Figure 7 above shows support levels among white voters in more detail, highlighting the past three Presidential elections and the 2018 midterm. The dominant takeaway, from our data and others, is that white college graduates and white suburban voters have turned solidly against Donald Trump’s Republican party.

In 2012, 46% of white college voters supported President Obama. We show a 4-point swing towards Clinton in 2016, some of which was certainly a backlash against Trump (other datasets show an even larger 2012-2016 swing), a continued swing towards House Democrats in 2018 (to 54% support), and a continued 54% level of support for Biden in 2020. White college women, who were evenly split in 2012, have been at 55% Democratic support or higher in the past three elections, topping out at 58% in 2020. While the levels of support among White College Men (50% Biden support in 2020), Urban White (66%), and Suburban White (46%) differ, the trends all point in the same direction, i.e., a substantial portion of this constituency moving solidly towards Democrats in the Trump era.

On the other hand, white voters without a college degree strongly supported Trump. In 2012, Mitt Romney enjoyed 60% support among this group, with Trump increasing those numbers to 64% support in 2016. 2018 saw a Democratic rebound here, with Republicans going back down to 60% support without Trump explicitly on the ticket. But in 2020, Trump did nearly as well, getting 63% support among white non-college voters as a whole.

We should emphasize that college education is not the only way to capture class, wealth or relative affluence. For instance, there are many relatively well off small business owners who vote Republican and have no college degree. Similarly, there are many teachers with advanced degrees who support Democrats and are underpaid compared to their highly-educated peers.

Religiosity and Evangelical Protestantism in particular are associated with voting for Republicans among white voters across education levels, and we hope to address this in future analyses.8 We focus on college education because granular Census data is available, allowing us to build detailed probabilistic models that we believe provide reasonable geographic accuracy.

Latino Voters Still Favored Democrats, but Republicans Made Inroads with Them, Too

The Latino vote has received much attention since the election concluded, and a full exploration of all of the nuances in their voting patterns is beyond the scope of this report. That said, our data does confirm topline voting patterns that have been seen in other data sources. First, to reiterate an earlier point, Latino voting levels rose dramatically in 2020, with the number of Latino votes rising by more than 30% compared to 2016.

Decreases in Latino Democratic Support, 2016-2020

Figure 8

Figure 9

Along with that, we find an 8 point shift in overall partisan support levels, going from 71% Democratic support in 2016, to 63% in 2020. Comparing presidential to midterm electorates is tricky, due to differences in the age and other demographics of who voted. But we found some of this drop between 2016 and 2018, with Latino support levels at 68% in the midterm.

Where was the drop in support concentrated? Figure 8 shows state-by-state estimates, focusing on Presidential battleground states. The biggest drop by far was in Florida, which is unique due to its large, but not exclusive, Cuban population. On the other end, Georgia and Arizona, which were critical to Biden’s victory, had a smaller drop from 2016 of 4 and 5 points, respectively. Other states fell in the middle.

On the right side, Figure 9 tries to make the Latino subgroup comparison more explicit. While we don’t have the necessary survey data to fully decompose Latino support levels by place of origin, we can get clues by using precinct-level election results.9For more detail, The New York Times has put together a nice interactive visualization of precinct-level election returns from 2016 and 2020. Here, we look at majority Latino precincts using our 2020 voter estimates and separate them using the dominant subgroup, according to the most recent Census data. We want to caution that this type of geographic analysis is not definitive, and only points towards trends that need to be further explored.10 By focusing on areas with majority Latino voters, we were better able to distinguish different ethnicities, but these areas only cover about ¼ of Latino voters overall. In other words, this analysis does not cover the majority of Latino voters, who live in non-majority Latino neighborhoods. It is also important to note the correlations between place of origin and state/region; for example Florida has the largest Cuban population, while the Northeast has a larger Puerto Rican population. The width of each bar represents how many voters come from these Census tracts. Similar to the state graph, this suggests that the biggest drop did indeed come in Cuban areas (13 points). But it also makes clear that this was not only about Cubans. Mexicans are the largest Latino subgroup in most states across the country, and highly Mexican areas also showed a drop (6 points), albeit smaller than Cuban areas. Puerto Rican, Dominican, and areas with other dominant groups were in the middle (8-9 point drop), close to the national average.

A critical question regarding the drop in overall Latino support is how much of the change was driven by vote switching, i.e., Latino voters who voted for Clinton in 2016 and Trump in 2020, and how much was driven by new Latino voters with different ideological and partisan preferences than existing voters. Answering these questions with certainty is incredibly difficult, as we will discuss in more detail later. But we see suggestive evidence that both of these factors played some role.

Latinos were disproportionately likely to be new voters, due to the massive increase in Latino voter turnout this year. Overall, 22% of Latino voters were first-time voters, who we haven’t seen in our entire database of general election voting going back to 2008. By contrast, just 14% of the national electorate was entirely new. When we take a more expansive view of new voters, including people who were new to voting in a given state compared to 2016, a full 40% of Latino voters were new presidential voters, while the national number is 29% of the overall electorate.

With such a large number of new Latino voters in the electorate, it is plausible that they drove a big part of the change in Latino’s overall support numbers. As marginal voters enter into the electorate, their partisan preferences may move closer to a 50 / 50 split naturally. Political scientists have long noted that marginal voters are less ideologically motivated or consistent in their voting preferences. Needless to say, this is only a theory and a complicated topic. Thus far, in our own data and others’, we have seen mixed evidence on this point, and we think it necessitates much further exploration.

We will return to the topic of new voters, and the difficulty in precisely measuring their voting patterns, later on.

Black Voters Key to Winning Coalitions

Next we turn to Black voters, who overwhelmingly supported Biden and Harris with 90% of the two-way vote. While Black voters are the demographic group with strongest Democratic support levels by far, we estimate a slight drop in support levels from 2016 (93%) and 2012 before that (97%, when President Obama was at the top of the ticket).

Despite this modest drop in overall support levels, increased voter turnout was particularly important among Black voters. For a demographic group that consistently supports Democrats at around 90% or more, higher voter turnout makes a major difference. On balance, slightly lower support levels with substantially higher turnout yielded more net Democratic votes from Black voters as a whole in 2020 compared to 2016.

This was true nationally, and was also true in key battleground states, as shown in Figure 10. These are the six closest states that Biden won, meaning they are the states where increased voter turnout among Black voters was the most critical component of his overall victory. In Georgia, Biden won by just over 11,000 votes. The margin that he got from Black voters was over 1.2 million votes, indicating that he had no chance in Georgia without this key constituency. This is true in Georgia, all of the states listed here and many other states across the country, and is not new in 2020. Needless to say, Black voters are key to Democratic success.

Figure 10: Vote Margins among Black Voters in Battleground States

| State | Margin of Victory | Margin from Black Voters | Larger than Victory Margin | Increase Over 2016 | Larger than Victory Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA | +11,779 | +1,262,820 | Yes | +199,773 | Yes |

| AZ | +10,457 | +127,567 | Yes | +28,458 | Yes |

| WI | +20,682 | +125,791 | Yes | +3,202 | -- |

| PA | +80,555 | +543,593 | Yes | -4,190 | -- |

| NV | +33,596 | +88,129 | Yes | +11,681 | -- |

| MI | +154,188 | +503,530 | Yes | +7,045 | -- |

The last set of columns reveal the more subtle point, that despite slightly lower support levels, the Democratic margin actually went up from 2016, due to higher black turnout. Again using Georgia to drill down: higher black turnout yielded an additional 200,000 net votes for Biden, above and beyond the margin that Clinton got from black voters in 2016. This was key to winning the state, as Trump would have handily won the state without the extra 200,000 net votes.11 This is also possibly true in Arizona, though the relatively small numbers there have enough uncertainty around them to leave us unsure.

When considering the 90% Biden support number among Black voters, we should consider the impact of new marginal voters (people who voted for the first time in 2020). As with Latino voters, it is plausible that new marginal voters entering the electorate for the first time naturally drove the overall support numbers slightly down, because these new voters are less ideological than long-time voters. Mathematically, this phenomenon would be more noticeable for Black voters, because it is easier for even slightly less supportive new voters to chip away at an average support level that is above 90%. We have seen some evidence supporting this, with new black voters in the high 80% support range, although these measurements come with substantial uncertainty because they are focused on a relatively small part of the overall electorate.

Asian American & Pacific Islander Voters Dramatically Increased Turnout

Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) voters had remarkably high turnout. Overall, AAPI voters comprised 4% of the electorate, but the number of votes from this group increased a staggering 39% from 2016. AAPI voters remained strongly supportive of Democrats, delivering 67% vote share to the Biden-Harris ticket. This is largely consistent with past elections. For instance, in 2012, this group favored Barack Obama with 66% vote share and cast ballots for Hillary Clinton at a similarly high rate of 68%.

The Urban-Suburban-Rural Divide

Figure 11: Democratic Vote Share by Urbanity, 2008-2020

Figure 11 shows the relationship between urbanity and vote choice for the past four Presidential elections and the 2018 midterms. It is unclear exactly where to draw the line to define an area as rural, suburban, or urban,12 We use the metric shown here: population density on the census tract level (or zip code where we don’t know census tract). These geographies are put into percentile order, on a 0-100 scale. We define rural, suburban, and urban areas using 25% and 75% cut-points on this scale, which creates groups that roughly correspond to the sizes of self-reported urbanity found in surveys. but here we can see that simple population density is strongly predictive of partisan preferences. The left side of the graph shows the least densely populated, most rural areas. Obama did the best out of all Democrats here, especially in 2008 when he got 41% support in rural areas overall. In 2016, Trump gained a lot of ground here, and Clinton dropped to 32%. House Democrats rebounded a little bit in 2018 to 36%, but this appears to have been a temporary shift, with these same rural areas dropping back to 33% Democratic support in 2020, when Trump was again at the top of the ticket.

Moving to the middle of the graph and the suburbs, we see a consistent gain for Democrats over the Trump era, going from 51% Democratic support in 2016, to 54% in 2018 and 2020. In other words, Biden was able to maintain the gains that Democrats enjoyed in the suburbs in 2018. In cities, on the other hand, Biden lost a little bit of ground compared to the midterm. While the densest urban areas remain deep blue, Democratic support peaked in 2016 and 2018 at 75%, and fell slightly to 72% in 2020.

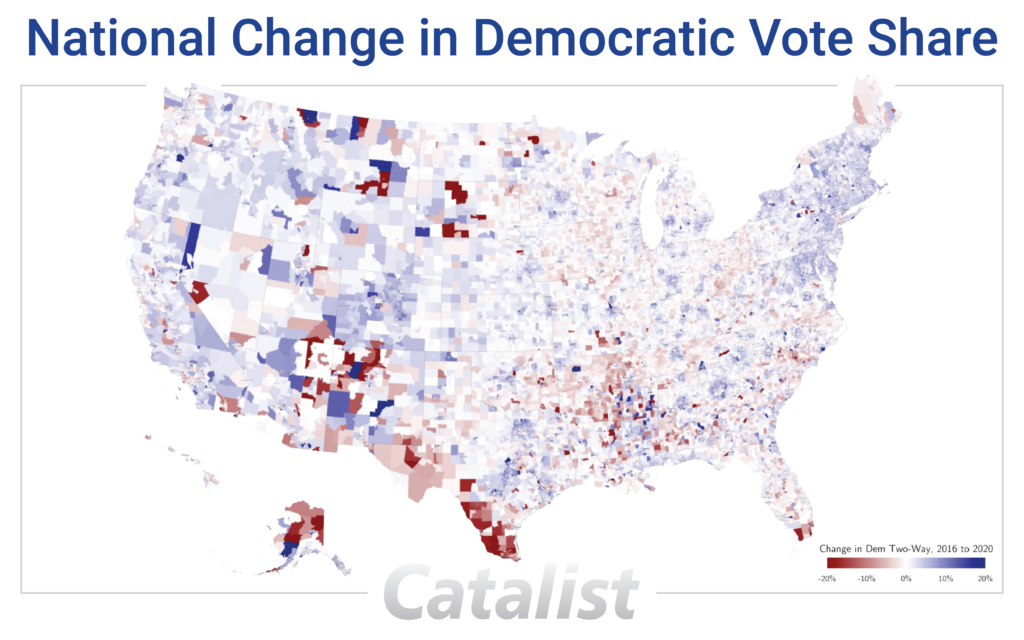

Figure 12: Increasing Racial Diversity and Voting Change, 2016 to 2020

While Democratic gains in the suburbs have been well documented, the nature of those changes is complex and often misunderstood. Part of it has to do with an increase in Democratic support among white suburban voters, as described earlier. But another part is a result of the changing demographics of the suburbs as a whole. The country is becoming more diverse, and many suburbs are changing as a result. Figure 12 shows how the numbers are changing among voters, comparing 2016 to 2020. Democratic support numbers are shown in red, explicitly showing the changes that were just discussed. Overlaid on top of that is the change in demographic distribution, grouping voters of color together as a whole. Many areas of the country are becoming more diverse, and there is quite a bit of overlap between those areas and areas where Democrats have seen consistent gains. The relationship is not simple, of course, as urban areas are also getting more diverse and shifted away from Democrats in 2020.

To this last point, we can’t divorce analysis of the 2020 electorate from the economic and policy consequences of the pandemic. We know that cities were hit hardest by the pandemic in many ways. COVID-19 hit dense urban areas first, and many people fled cities as a result. Unemployment shocks hit hardest in urban areas, particularly among Black and Latino workers.

Women

Gender Gap in Turnout and Vote Choice

Figure 13

Figure 14

Women remain a core part of the Democratic coalition. We see this in two ways, in Figures 13 and 14. First, women are a larger share of the voting electorate than men, comprising 54% of the voting electorate in 2020. Their relative size advantage over men has stayed consistent, in the 53-55% range, over every election in our database (2008-2020). While women vote more regularly than men overall, this is especially true for Black women (59% of Black voters overall) and Hispanic women (56% of Hispanic voters overall).

We also estimate a gender gap of about 10 points – 57% Biden support among women overall, 47% support among men. Part of this has to do with racial composition, as described above, but the gender gap also holds within each racial group – ranging from about 7 to 13 points depending on the group.

Third Party Voting Declined

Figure 15: Three-Way Vote Share by Age, 2016-2020

| Age | 2016 | 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Dem | Rep | Third | Two-Way | Dem | Rep | Third | Two-Way |

| 18-29 | 55% | 34% | 10% | 62% | 60% | 37% | 3% | 62% |

| 30-44 | 52% | 40% | 8% | 56% | 56% | 41% | 3% | 58% |

| 45-64 | 46% | 50% | 5% | 48% | 47% | 52% | 1% | 48% |

| 65+ | 45% | 52% | 3% | 46% | 48% | 52% | 1% | 48% |

Two-way vote share doesn’t tell the whole story when it comes to young voters. Third party voting was incredibly high in 2016, with third party candidates capturing 6% of votes overall. This was concentrated among young voters, 10% of whom voted third party, and was highest for young white voters, 13% of whom voted third party. 2020 was a different story, with third party vote share falling to < 2% of the vote overall. As the prevalence of third party voting fell, young voters had the furthest to fall, dropping from 10% to 3% support for third party candidates. Young white voters went from 13% third party support to 3%. Because of this, even though the two-way partisan split was similar across both years, Democrats did better among young people in 2020.

Democratic gains among young voters were important in terms of their partisan voting patterns, and they were especially important when you consider the growth in turnout. We turn there next.

New Generation of Voters

The 2020 election was historic in its level of voter turnout. When we look at composition of the electorate by age, we see a slight increase in the percent of the electorate under the age of 30, going from 15% in 2016 to 16% in 2020. While this increase directionally lines up with what we would expect, the change seems modest given the circumstances.

It turns out that looking at composition by age substantially understates the magnitude of the change in this election. Age data can be confusing because substantial portions of the electorate “age out” from one group into another. For instance, 6% of voters were between the ages of 30 and 33 in 2020, meaning they moved from the 18-29 group, a common cutoff for discussing “young” voters, to the 30-44 group.

Figure 16: Turnout by Generation, 2016-2020

We can see what is happening more clearly by looking at birth year or generation. In short, 2020 accelerated a massive change in the composition of the electorate, with Millennials and Gen Z taking an increasingly prominent role in the future of American elections – a demographic change that is functionally permanent. Figure 16 shows the data year-by-year. Turnout increases were clearly largest among the youngest generation. In terms of raw number of votes, Gen Z increased their total from 2016 by nearly 300%, since many were under 18 and therefore ineligible in 2016. Millennials were the second largest increase at 27%. The turnout increases by generation continue to decline from there. The “break even” point is around age 70, with people born in the 1940s or earlier declining in terms of raw number of votes.

Figure 17: Share of the Electorate by Generation, 2008-2020

2020 continued the natural and expected generational turnover from election to election, slightly accelerating it due to the historic levels of turnout. Figure 17 shows the change over the last four Presidential elections. In 2008, even with high levels of young voter engagement for President Obama’s first election, Millennials accounted for only 14% of the electorate, while the Baby Boomers and older group accounted for over 60% of the electorate. Those numbers have been steadily changing over time. By this past election, the youngest two generations represent nearly one out of three voters, while the older generations (still the plurality) are down to 44% of voters.

Figure 18: Vote History of the 2020 Electorate

| Group | Same State? | Millions of Votes | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voted in 2016 | Yes | 113.9 | 71% |

| Voted in 2016 | No | 4.3 | 3% |

| Voted in 2018 | Yes | 11.7 | 7% |

| Voted Pre-2016 | Yes | 5.8 | 4% |

| Fuzzy Match 2016 | Yes | 1.8 | 1% |

| First-Time Voter | -- | 22.2 | 14% |

| Total | -- | 159.7 | 100% |

The voter file lets us look at the changing electorate in more detail than by using demographics alone. Here, we use our detailed archives and record linkage system to estimate how many new voters there were in 2020, and how much turnover occurred in the electorate from 2016 to 2020.

Importantly, analysts and campaigns define “new voters” differently and there is some uncertainty in any national record linkage system when attempting to identify entirely new records. With that in mind, we can show some of the nuances in analyzing this question, as is done in Figure 18 above. According to our data, 71% of 2020 voters also voted in 2016, in the same state over both years. That means that 29% of voters were “new presidential voters” in the state in which they cast their ballots. But those 29% of voters break down into various categories:

- 3% voted in 2016 in a different state, meaning they moved in the intervening 4 years

- 7% voted in the 2018 midterm but not in 2016

- 4% are longer term repeat voters: they sat out both 2016 and 2018, but they did vote in at least one even-year general election since 2008

- 1% are “fuzzy matches” within a state. This category recognizes that no record linkage system is perfect and includes a more expansive view, trying to find 2016 voters based on either their (a) first name, last name, birth year or (b) first initial, last name and exact birthdate. Some of these voters may have in fact voted in 2016, but it is a small enough group that it doesn’t affect our substantive conclusions.

- 14% are first-time voters, meaning they did not vote in any even year election going back to 2008.13Some of them were registered in previous years but did not vote in those elections.

Some of these categories could be defined slightly differently, but we feel this paints a reasonable picture of who might be considered new voters in 2020.14For example, in this table we only consider even-year general elections. We could use primary or special elections, or general elections in odd years. We also chose the ordering of this table to specify the most relevant groups; if things were ordered differently, then the numbers would change. For example, there are some 2018 voters who also voted pre-2016, so if we reversed the order of those categories then each group’s numbers would change slightly. Lastly, a national “fuzzy match” would find 2016 voters that voted in other states, but would also have a high false positive rate, i.e., inappropriately move too many people out of the “first-time voter” category.

Figure 19: Percent of Battleground State Electorates that are New Voters15See text for details on how these groups are defined. Wisconsin and New Hampshire have asterisks, to note that age data is missing from the raw voter file for unusually high portions of each of these states’ voter files. This impacts our record linkage system and creates more uncertainty for the numbers in these states.

Figure 19 shows these numbers in key battleground states, highlighting important differences across the country. The bottom line is that the number of new voters is substantially higher across the Sunbelt, particularly in the Southwest. In both Nevada and Arizona, about 20% of voters were true first-time voters, compared to 14% nationally. If we look at the overall turnover from the last presidential election to now, over 35% of the voting electorate is different in these two states, i.e., new presidential voters. Texas, Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina all have new voter rates that are at or above the national average, too. Michigan’s rates are near the national average, but there appears to be less turnover in the other Midwest battleground states and New Hampshire.

The fact that new voting rates are higher in the South and West is fairly unsurprising, considering those states’ migration rates and demographics. But the magnitude of these changes is poorly understood: we don’t think many people realize that state-level turnover from one Presidential election to the next can be as high as 35% or more.16We conducted a robustness check of our numbers by doing a “fuzzy match” on all non-2016 voters, i.e., changing the ordering of the rows in Figure 18. If we consider any “fuzzy match” within the state to be a 2016 voter, this only changes the numbers by 2-3 percentage points nationally, with some state-level variation. From our standpoint, even if our numbers are off by 10 percentage points, this would still justify substantial consideration regarding the issues that we discuss here. We think this has important and wide-ranging implications to election analysis, and deserves a great deal of further scrutiny and analysis. To give three prominent examples:

- Why are elections so stable from one Presidential election to the next? Battleground states are defined with a lot of emphasis on the last election result, and county-level election results are quite stable from one year to the next. How does this happen with this high level of turnover from one year to the next?

- How should this affect poll weighting, which is largely based on the composition of the electorate from four years prior? To be clear, it does not appear as though polling errors were larger in states with more turnover, and in our view this was not the main source of polling error in 2020.

- How does this affect strategic and tactical considerations for political campaigns and civic engagement organizations? Many practitioners and analysts think of election changes as occurring within a largely similar group of people from one election to the next. People understand that changes occur, with young voters coming into the mix, voter persuasion, differential turnout rates, and so on. But this standard mental model usually breaks out voters into separate categories: brand-new registrants, reactivating inactive voters, voters who first voted in the last midterm, and movers, for example. The implications of the total amount of election turnover are more rarely considered.

Figure 20: New Presidential Voters by Age Group

| group | newvoters | Composition | Biden Two-Way (Tentative) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | % New Voters* | 2016 Voter | New Voter | 2016 Voter | New Voter |

| Total | 29% | 100% | 100% | 51% | 56% |

| 18-29 | 64% | 8% | 35% | 62% | 62% |

| 30-44 | 34% | 21% | 27% | 57% | 58% |

| 45-64 | 21% | 39% | 26% | 48% | 48% |

| 65+ | 14% | 32% | 12% | 48% | 50% |

One important question that immediately follows this line of thinking is, how Democratic or Republican-leaning are these new voters, compared to returning voters? We have suggestive data to try to answer this question, but we want to strongly caution readers that we consider these results highly tentative.

According to our tentative estimates, new presidential voters supported Biden at substantially higher rates overall (56%) than 2016 voters who returned in 2020 (51%). This appears to be driven primarily by their demographic distribution. Consider the age breakdown shown above: there are few differences between 2016 voters and new presidential voters within each age group, but new voters skew much younger and more Democratic. On top of this, new voters were more racially diverse than returning 2016 voters, with 40% of Latino voters, and 42% of Asian voters being new presidential voters.

Why do we consider these findings tentative? In short, these breakdowns are built off of complicated survey models, and we are unsure as to whether the survey data is sufficiently representative to draw firm conclusions. As an example, consider the estimates shown here among 18-29 years. Raw survey estimates show fairly similar partisan breakdowns, but we are cautious because the majority of young survey respondents are 2016 voters, as opposed to the 65% of young voters who show up as new presidential voters across the entire voter file. Survey respondents tend to be people who are more politically active, so this divergence is unsurprising. But it does give us pause in terms of how much to trust the estimates coming out of the survey data.17To be clear, our statistical models are specifically designed to overcome problems in non-representativeness, but nothing is magic; our experience in building and using these models over time has taught us to be cautious when dealing with these types of issues. Additionally, we’re not aware of other data or research that would allow us to validate this finding, which makes us particularly cautious about these numbers. In other words, it would not surprise us if the support differences between 2016 voters and new presidential voters was slightly lower or higher than the 5-point difference shown here.

It is also important to emphasize that we do not necessarily expect these new voters to signal a new, enduring Democratic majority, with ever-more Democratic-leaning new voters building larger and larger Democratic leads election after election. The flip side of the coin shown here involves people who dropped out of the electorate, who may be more Democratic than the electorate as a whole. This is plausible if they are more likely to move around, face barriers to re-registering and voting, or are less likely to be consistent voters for any other reason. Needless to say, we consider this an important area of future exploration.

Regardless, this data is suggestive that a good deal of Biden’s support level was driven by new voters, who are younger and more diverse than returning voters from four years ago.

Conclusion

The 2020 election was incredibly challenging and full of surprises. For the second presidential election in a row, voters defied the public polls, delivering a clear victory for Democrats, but one that was closer than many analysts expected and at a time when the two major political parties are divided on the nature and value of democracy itself.

Upon taking the oath of office, in the wake of a violent attack on the Capitol, President Biden noted that democracy is “precious” and “fragile.” As the last four years have made clear, it’s also incredibly dynamic. Despite two relatively close results, the electorate that showed up in 2020 was markedly different from the electorate that showed up in 2016. The electorate will shift again – perhaps significantly – in the midterms and in the 2024 presidential election.

We believe that voter files like the one Catalist maintains will remain vital for understanding the electorate as people choose whether to cast ballots in these coming elections. Campaigns and civic engagement organizations have an opportunity to keep these new voters engaged. At the same time, small differences in turnout and vote choice can have big consequences, as Democrats’ victory in the Georgia Senate runoffs demonstrated.

We’ll continue to update these analyses over the coming months and are excited to share more analysis, including closer looks at some swing states.

Methods

While there is no perfect way to understand the electorate, we believe our research offers a particularly robust review, because we can analyze results from the vantage point of the Catalist database.

Catalist is a progressive data utility that works with public interest organizations and Democratic campaigns. We have been collecting and maintaining a national voter registration database – usually called a voter file – for more than 15 years. Broadly speaking, voter files provide a detailed view of the electorate, because they include the full list of people who voted in an election, collected directly from each chief election official in the country – when it comes to understanding voter turnout, this is not a survey, and it’s not a sample.

Voter file databases also vary in their methods and approach. Many voter files emphasize individual-level accuracy, optimizing for political marketing in a given election cycle. While we certainly do this at Catalist, we also realize that special attention and methods are needed to provide an accurate, or even reasonable, aggregate view of the electorate. We’ve invested a lot of time in trying to tackle these specific problems, with an emphasis on accurate aggregate-level statistics over time. The Catalist voter file represents hundreds of thousands of hours of work collecting, processing, and verifying information over a decade-and-a-half of dedicated research. Our process supplements the voter file with large-scale survey data, precinct results collected as widely as possible, and statistical modeling meant to tackle these specific challenges. Our results are not going to be perfect – nothing is – but we feel these efforts pay serious dividends, and give us a unique perspective on what happened in this election.

At the moment when we “froze” our data analysis for this report, individual-level vote history was collected and processed for 46 states. These states’ data, alongside early vote data that was collected in the remaining five states, represent 97% of voters in the country. We use pre-election expectations, corrected with geographic election turnout results, to project turnout for the remaining 3% of voters. In terms of Biden vs. Trump vote share, precinct results have been collected and matched for geographies representing roughly 59% of voters, including most of the top-tier Presidential battleground states. For remaining voters, we use data from pre-election expectations, survey modeling, and county election results to project the remaining results. We do not expect our results to substantively change when the remaining data is collected and processed.

Finally, some readers may recall that we published a similar series after the 2018 election, which included data points for 2018 and earlier years. Post-2020, we completely rebuilt and revised all of our historical estimates, based on newly available data and statistical methods. Our earlier data points have not changed dramatically as a result, but it is important to note that some numbers have changed. While this approach may be new for some readers, we feel it is important to provide revised estimates, so that the numbers are as comparable as possible across years. For more information, please see our recent AAPOR conference talk on these topics.

More from Our Partners and Other Analysts

According to EunSook Lee, Director of the AAPI Civic Engagement Fund: "AAPI turnout jumped by 39%, in part due to the incredible work of AAPI community groups from Georgia to Michigan to Pennsylvania, and all points in between. The rise in anti-AAPI violence also contributed to increased motivation among AAPI voters who used the ballot box to fight back against racist rhetoric from Trump and his supporters. We know from talking to AAPI groups who are building power in our communities that this momentum will only strengthen as we head into the midterm election." The organization’s research includes a 2020 American Election Eve Poll and a report on Activating the APPI Voting Bloc.

CIRCLE, the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement, is a non-partisan, independent research organization focused on youth civic engagement in the United States. They estimate that half of young people voted in 2020, an 11 point increase from 2016. Their 2020 Election Center includes more analysis of the youth vote by region and state.

Equis Research, which deeply studies the Latino electorate, found that turnout and persuasion effects both played a role in the 2020 results. Their research emphasizes the diverse nature of the Latino electorate and is based on more than 40,000 interviews with Latino voters.

A Third Way analysis of House-level data found that Democratic House candidates endorsed by the NewDem Action Fund had higher relative gains from 2016 compared to other Democratic candidates in their respective districts.

AAPI Data, a publisher of demographic data and policy research on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, previously wrote an analysis of turnout among Asian-Americans.

Grecia Lima, Political Director for Community Change Action, a national organization that builds the power of low-income people, especially people of color, said the report “shows clearly how a multi-racial coalition of Black, brown and immigrant voters is radically transforming our nation’s electorate. At Community Change Action, we are committed to engaging these new voters and low-propensity voters who are coming together for each other to usher in leaders that will help create a more progressive vision for our families where we can all thrive.” The organization’s 2020 Election Report summaries its work reaching more than 13.9 million voters.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and GSSA issued a detailed memo in response to this analysis—citing additional research from HIT Strategies. They found that the increase in Black turnout was “due in large part to the heightened interest in and concerns about the direction of the country and its personal impact on Black Americans, which translated into eagerness to vote.” The organizations worked with more than 200,000 volunteers to contact an estimated 11 million Black voters in the 2020 cycle.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Catalist?

Catalist is the longest-running data trust in progressive politics. We work extensively in the civic engagement space, providing data, analytics, and technology to public interest organizations, researchers, media outlets, and Democratic campaigns. Catalist is owned by a trust and never sells information for commercial purposes. It maintains one of the largest and longest-running voter files independent from the two major political parties.

Why are these numbers different from other sources, like the Exit Poll, AP VoteCast, and the Current Population Survey?

Each of these data sources uses a different approach to understand the electorate, and none of them, including our approach, is perfect. For example, the Exit Poll uses a combination of in-person precinct sampling and in-person interviews, along with survey data to capture the early voting electorate. The Current Population Survey is a large-sample national survey conducted by the U.S Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, where voting and registration questions are added to their monthly “jobs report” surveys.

Our approach is different, as is described in our Methods section and related AAPOR report. We use our voter registration database, along with statistical models built to understand the demographics and partisan distribution of the country. For related academic work, see here for a simplified version of the type of methods that we use.

Will you publish state or district-level numbers or make finer-scale data available?

Like any organization, we have limited time and resources for conducting analyses like these and making the results public. Analyzing and verifying finer-scale data is time-consuming and labor-intensive, though we’ve done so for a variety of private and publicly-facing projects. Since 2018, we have published these national numbers following major general elections to inform our collective understanding of the electorate. If you would like access to more detailed data, please contact us at press@catalist.us.

Does voter file-based research report margins of error the same way polls do?

Publishing a reliable margin of error is outside the scope of our project, and we are very skeptical of published margin of errors in surveys, including in the context of other post-election data sources. Margin of error calculations typically attempt to convey the uncertainty around an estimate, but they often rely on assumptions about the data that don’t hold. They are sometimes calculated based on sample size alone, ignoring the reality that surveys are not truly random samples, an increasingly important concern in today’s changing polling environment. With added complexity, margin of error calculations can also try to account for survey design aspects like response rates, random sampling of precincts, weighting, and other factors. Our view is that these often do not capture the full range of uncertainty. This is true for survey estimates overall, and particularly true for model-based estimates like the ones we present here. For more discussion on model-based estimates, see the Discussion section here (page 22).

What can (and can’t) this data tell us about turnout vs. persuasion effects?

In our analysis of the 2018 election, we tried to explicitly decompose the impact of differential turnout versus changing vote choice to explain changing election results from one year to the next. We decided against publishing a similar analysis in this report, for two reasons:

- Our report in 2018 repeatedly and strongly emphasized that both turnout and vote choice played an important role in Democrats’ victory: (a) the spike in Democratic turnout compared to past midterms made the electorate demographically similar to 2016 which was incredibly important, and (b) changing vote choice among 2016 voters pushed things even more in the Democratic direction. Point (a) was lost to many, because our “decomposition” calculation used 2016 as a baseline, and was explicitly comparing that 2016 (Presidential) election to the 2018 (midtem election).

- In retrospect, we consider the “percent impact” number we developed to be a noisy indicator of the impact of persuasion vs. mobilization. The number divides one small number (the impact of turnout or changing vote choice, based on survey-driven estimates) over another small number (the change from one election to the next). From 2016 to 2020, we would be trying to decompose a 2-point margin change (the denominator), using a numerator with too much uncertainty around it. In other words, small changes in our estimates could lead to large-looking changes in the “percent impact” numbers.

Because of these two factors, we think it is more prudent to lay out the various factors in more descriptive terms, as we’ve done in this report. For more information on why we consider some of these numbers to have substantial uncertainty around them, see details in the New Generation of Voters section. Overall, we know that people’s enthusiasm to vote and their propensity to cross over to vote for a different party or candidate than they have previously can be closely related. We’re interested in developing more sophisticated and rigorous methods for decomposing this effect, and are interested in working with researchers who have interest in studying this more going forward.

How do demographic models like this one differ from other measures of demographics?

Raw voter files have incomplete coverage on key demographic variables, so accurate statistical models are key to the success of this type of analysis. Most standard demographic models on voter files are optimized for individual-level accuracy, not for aggregate statistics. Our models place special emphasis on producing accurate aggregate-level statistics over time. See here for more detail.

Despite our efforts, other high quality data sources show different demographic breakdowns for the electorate. On race specifically, the Census asks respondents to provide race, two or more races, and Hispanic origin. For the purposes of Catalist’s aggregate analysis of the electorate, our models assign records to one racial category each based on the best available data from voter file records and surveys. In addition to white, Black, Latino and AAPI voters, we also aggregate statistics into an Other category that includes voters who are multi-racial or Native American, among other groups. These categories and related subcategories can be further analyzed at a local and state level, though for the purpose of this analysis they are discussed as national-level aggregates.

How did mail and other early voting affect the election?

Early voting hit record highs in 2020, with over 101 million people casting their ballots early, either by mail or in person. This was a major factor in the election, at the very least by allowing safe voting options for millions of Americans in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fully analyzing the impact of these changes on the election is a large task, and we did not feel we could do it justice in the confines of this report. Given sufficient interest, we may tackle this subject in more detail in a follow-up report.

How much can Catalist share about its methods and data sources?

Because Catalist works with campaigns and political organizations, much of our data is proprietary and we are careful not to expose all of the details. However, we’re also data scientists and social scientists, and we believe that sharing our research can help inform our collective understanding of the electorate. To that end, we publicly share the results of our analysis, including through the What Happened series, and regularly collaborate with academics and other researchers. We’ve also published academic papers, conference talks, and FAQs to provide transparency about the basic concepts of our approach.

How can I get access to Catalist’s data?

Catalist’s data is based on more than 15 years of partner organizations working with – and mobilizing – millions of voters. We work with progressive organizations, research organizations, universities, media outlets, and also collaborate with academic researchers who study the electorate. If you’re interested in learning more, please email press@catalist.us.

What Happened™ Catalist © LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Proprietary data and analysis not for reproduction or republication.

Catalist’s actual providing of products and services shall be pursuant to the terms and conditions of a mutually executed Catalist Data License and Services Agreement.