What Happened™ in 2022

Arizona and Michigan

The 2022 midterm election resulted in significant victories for Democrats despite the historical expectation that a party controlling the presidency and both chambers of Congress faces a midterm backlash from voters. Democratic overperformance was especially evident in states with highly contested Senate and Gubernatorial races, where electorates looked similar to 2020 and 2018. However, winning coalitions differed across battleground states based on both the demographic composition of the states themselves as well as important differences in how campaigns and voter outreach organizations conducted their work.

Catalist’s national-level What Happened 2022 analysis focuses on what we can glean from our national voter file. This report focuses more narrowly on highly contested statewide elections in two important battlegrounds: Arizona and Michigan.

Battleground states differ demographically and politically from the country as a whole, with Arizona’s electorate reflecting demographic changes in the Sunbelt and Michigan representing the Midwest “Blue Wall” states that flipped to Trump in 2016 and back to Biden in 2020.1In 2020, we similarly examined Nevada and Wisconsin.

When comparing these results to our national What Happened analysis — as well as changes across years and groups — we caution readers that statistical analysis of smaller populations and subpopulations comes with more uncertainty. These uncertainties grow at the state level. Catalist’s approach uses a pooled model, meaning estimates are derived from national models, granular election results, survey data in states, demographic modeling, and other building blocks. In our analysis, we also pay close attention to each state’s unique administrative data regimes, particularly variations in each jurisdiction’s public voter file.

Data Guide

Catalist has produced a data guide to accompany its What Happened series.

Arizona and Michigan are also ripe cases for in-depth state-level analysis. Both states went for Trump/Pence in 2016, but Biden/Harris in 2020. In 2022, they each had heavily contested statewide races in the 2022 midterms: in Arizona, the Senate race between Democrat Mark Kelly and Republican Blake Masters and the Gubernatorial race between Democrat Katie Hobbs and Republican Kari Lake; and in Michigan, the Gubernatorial race between Democrat Gretchen Whitmer and Republican Tudor Dixon. Michigan also had a statewide pro-choice ballot initiative, one of many contests where voters pushed back against Republican-appointed Supreme Court justices overturning Roe v. Wade. Looking ahead, both parties are expected to remain focused on these states as presidential and senate battlegrounds in 2024.

Beyond their clear electoral importance, Arizona and Michigan also enable investigations into broader regional trends in the Sunbelt and Midwest, respectively, which are expected to remain battlegrounds in upcoming election cycles.

About Catalist

Catalist operates as a trust, with a board comprised of major unions, progressive organizations and data specialists with years of experience in Democratic and progressive campaigns. Catalist is the first and only unionized data firm in its field (Catalist Union, Communications Workers of America Local 2336).

Arizona

Arizona was historically a red state, but one where voters — particularly white voters — have favored candidates with an independent streak, notably former Republican Senator John McCain. At the same time, the state’s population has been growing and diversifying, making it increasingly competitive, with Democratic candidates sweeping top-of-ticket statewide offices over the past several election cycles.

Race

Arizona’s population is more heavily Latino and Native American than the United States as a whole, with relatively lower shares of Black and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) voters. The relative size of its white voter population is roughly similar to the country as a whole.

Figure 1. Composition of the Arizona and National Electorates by Race, 2022

In this analysis, we focus on the Latino population because it is so disproportionately large compared to the country as a whole and especially compared to other swing states. By contrast, limited data on Black, AAPI, Native American, and voters of other racial groups make statewide analyses more difficult and uncertain.

Latino Voters

Latino voters composed 15% of Arizona’s voting electorate in both 2018 and 2022, making Arizona the state with the 4th largest Latino share of the voting population in 2022, behind only New Mexico, Texas, and California.285% of Arizona’s Latino Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) is of Mexican origin according to 2020 American Community Survey data By comparison, Latino voters only comprised 9% of the national electorate in 2018 — falling to 8% in 2022 — meaning that the Latino share of the vote in Arizona is nearly twice as large as in the country as a whole.

Two-way Democratic support declined among Latino voters in Arizona between 2016 and 2020, but less steeply than it declined nationally. In Arizona, support fell from 69% in 2016 to 63% in 2020. However, Latino voters nationally dropped from 71% support for Clinton/Kaine in 2016 to 62% support for Biden/Harris in 2020.

The 2022 midterms also saw stable or increased levels of Democratic support among Latino voters in Arizona compared to 2020. Latino voters supported Democratic Senate candidate Mark Kelly at an especially high rate, with a two-way Democratic support share of 68%. Down-ballot House races also attracted Democratic support shares that were higher than Biden/Harris margins in 2020. By comparison, Latino voters nationally remained stable in their Democratic support between the 2020 Presidential race and 2022 House contests.

Table 1. Vote Share and Democratic Support among Latino Voters in Arizona, All Voters in Arizona, and Latino Voters Nationally

| Percent of Voters | Dem Support (Two-Way) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2022 | 2016 Pres | 2020 Pres | 2022 Gov | 2022 Sen | 2022 House | |

| Arizona Latino | 15 | 15 | 69 | 63 | 64 | 68 | 66 |

| Arizona Total | -- | -- | 48 | 50 | 50 | 53 | 49 |

| National Latino | 9 | 8 | 71 | 62 | -- | -- | 62 |

There are many reasons why Latino voters in Arizona may have shifted less severely against Democratic presidential candidates between 2016 and 2020 compared to Latino voters nationally.

First, the demographics of the Latino electorate in Arizona are worth examining. Latino voters in Arizona are younger than Latino voters nationally. In the 2022 midterms, Latino voters aged 18-29 and 30-44 composed 20% and 27% of the Arizona Latino electorate respectively, with these groups composing only 12% and 25% of the Latino electorate nationally. By contrast, Latino voters aged 45-64 and 65+ made up 33% and 20% of the Arizona Latino electorate, compared to 38% and 25% of the national Latino electorate.

Figure 2. Composition of the Arizona Latino Electorate by Age, 2022

Latino voters in Arizona are also less urban and more suburban than Latino voters nationally, though the Arizona electorate overall tilts even more strongly toward less urban and more suburban voters. In 2022, 27% of Latino voters in Arizona were categorized as urban, compared to 38% of Latino voters nationally. Higher rates of suburban residence offset this 10-11 percentage point difference: 60% of Arizona Latino voters were categorized as suburban, compared to 50% of Latino voters nationally.

Figure 3. Composition of the Arizona Latino Electorate by Urbanity, 2022

Beyond age and urbanity, additional demographic factors can help us understand shifts in Democratic support within the Latino electorate in Arizona more clearly.

Overall, younger Latinos without a college degree were most likely to shift toward Republicans between 2016 and 2020. But this group votes less frequently than Latinos with four-year college degrees, making comparisons between higher turnout presidential years and lower turnout midterm years more difficult. Specifically, voters who are more likely to swing from one party to another vote less frequently than voters who are strong partisans.

The Equis Research 2022 Post-Mortem points to an important leading indicator: 2022 Latino non-voters were much more likely to list the economy as their most important issue, a trait shared with 2022 Latino voters who supported Republican candidates. To be clear, these voters were not simply conservatives expressing negative opinions about the economy during a Democratic presidency. For instance, their concern about abortion was much higher than Republican voters’ and they did not register “the border” as a concern, but the focus on pocketbook issues that were mostly the focus of right-leaning voters seemed like a cause for concern.

Additionally, we find mixed evidence regarding partisan differences among consistent and returning voters. Matching survey data from the 2020 election to current voter history files, we find that Latinos who voted in 2020 but did not vote in 2022 reported supporting Joe Biden 6 percentage points less than Latino voters who turned out in both elections. But when looking at national survey data from 2022, the opposite is true: survey respondents who voted in 2020 but did not vote in 2022 were 2 percentage points more likely to recall supporting Joe Biden. This trend holds up in 2022 survey data from Arizona.

Table 2. Surveys of 2020 Latinos Who Did or Did Not Vote in the 2022 Elections

| Year | Geography | Voted in 2022 | Voted in 2020 | Biden/Harris Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | US | Yes | Yes | 70% |

| 2020 | US | No | Yes | 63% |

| 2022 | US | Yes | Yes | 62% |

| 2022 | US | No | Yes | 64% |

| 2022 | AZ | Yes | Yes | 53% |

| 2022 | AZ | No | Yes | 57% |

This analysis reinforces that Latino voters nationally and in Arizona have nuanced voting patterns that are not easily assessed by political analysts. Even high-quality datasets, like the one we present in Table 2, can differ in important ways. More research — and more campaigning — may help paint a clearer picture of how Latino voters are engaging.

The second set of reasons we explore focuses on campaigns and organizing.

Arizona has held a relatively high number of competitive statewide elections since 2016, requiring sustained investments in campaign infrastructure. These investments included sustained Democratic spending on Spanish-language advertising. According to Spanish language media tracking data compiled by Equis Research, Solidarity Strategies, and Priorities USA, Mark Kelly spent close to $16 million on Spanish language media, nearly 10 times as much as his opponent, Republican Blake Masters.3This broader research is not publicly available, but was shared with Catalist for analytical purposes and to help shed light on campaign strategies in Arizona. In contrast, in the Nevada Senate race, Catherine Cortez Masto spent close to $13.5 million on Spanish language media while her opponent Adam Laxalt spent a little over $6 million, meaning there was less of a disparity between Democratic and Republican spending. Arizona Republicans’ support for extreme anti-immigrant legislation in 2010 through the passage of SB 1070 also provoked a backlash and fostered long-term organizing that may have been absent in other states. Additionally, broader campaign factors may have played a role. The Biden/Harris campaign overperformed in Arizona generally, including among Latino voters.

Finally, theories of descriptive representation suggest that Latino candidates may have additional appeal to Latino voters. In 2022, Adrian Fontes was the Democratic nominee for Secretary of State and won his race against election denier and oath-keeper, Republican Mark Finchem. Fontes won with 53% of the two-party vote, outperforming non-Latino Democratic candidates for Governor and Attorney General. Heading into 2024, Democratic Representative Ruben Gallego, also a Latino, is likely to be the party’s nominee for the Senate and may have a strong appeal to Latino voters in particular.

Native American Voters

Arizona is unique demographically among battleground states for its large Native American population. The share of Arizona voters who identify as Native American is 3%, nearly 3 times higher than the 1% of Native voters nationally. Arizona ranks 3rd in the size of its Native American population nationally, behind only Oklahoma and California.

Unfortunately for the purposes of voter file analysis, Native American voters tend to be one of the most difficult subgroups in the electorate to survey and model. This is largely due to general difficulties related to studying voting patterns among smaller populations. For instance, a survey of Native voters that the Washington Post ran in 2016 required 4 months of surveying to compile just 500 interviews with Native American voters, something that is much easier to do for larger population groups.

Additionally, the address-based nature of voter file data makes it more difficult for these systems to have visibility into Native American populations, where voters often register through tribal offices or post offices on reservations rather than with unique fixed addresses such as apartments or single-family homes.

As a result, we do not have enough confidence in support estimates among Native American voters in Arizona to publish them as part of this analysis. That said, we continue to invest in data and research related to Native American voters and are eager to partner with funders and organizations on these efforts.

White Voters

White voters in Arizona are relatively older, more Republican, and have higher rates of four-year college completion than white voters nationally. These demographic dynamics are driven, at least in part, by well-off, college-educated retirees who are looking to take advantage of lower costs of living, warmer weather, and lower taxes.

Arizona’s white electorate stands out from white voters nationally in its higher share of older voters. Specifically, voters aged 65 and older comprised 42% of the Arizona white electorate relative to 36% of the national white electorate and 37% of all Arizona voters. This larger share of 65+ year-old voters is offset by smaller shares of voters from all other age cohorts.

Figure 4. Composition of the White Arizona and National Electorates by Age, 2022

White voters in Arizona are also less polarized by education than in other parts of the country. While Democrats lost support among white non-college voters in many states between the 2012 and 2016 Presidential elections, including the Rust Belt, they gained support in Arizona while also gaining with white college voters.

Figure 5. Democratic Support among White College and Non-College Voters in Arizona and Nationally, 2012-2022

However, white voters with four-year college degrees in Arizona started from lower Democratic support levels than their national counterparts. Comparing support for Biden/Harris in 2020 to support for Democratic House candidates in 2022, Arizona saw lower levels of Democratic support among white college voters compared to nationally. In Arizona, Democratic support shares among white college voters were 50% for Biden/Harris in 2020 and 47% for House candidates in 2022. By comparison, Democratic support nationally among white college voters was 55% in the 2020 Presidential election and 50% in the 2022 House contests. While the magnitude of this shift was larger nationally than in Arizona, Democratic support levels for 2022 House candidates remained lower among white college voters in Arizona than nationally.

Additionally, Senator Mark Kelly received a higher two-party Democratic support share (52%) than did Democratic House candidates nationally (50%) and in Arizona (47%). Kelly’s persistent overperformance with these voters in his elections may be unique to him and Arizona. Several factors could contribute to these dynamics that are largely beyond the scope of this analysis, including specific outreach Kelly’s campaign has conducted to these voters, the unique appeal former astronauts can have when they run for office, and his opponents’ relative weakness in multiple election cycles.4Kelly is the 4th NASA astronaut elected to Congress.

Table 3. Democratic Support Shifts among White College and White Non-College Voters, 2020-2022

| Arizona | National | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 Pres | 2022 Sen | 2022 Gov | 2022 House | 2020 Pres | 2022 House | |

| White College | 50 | 52 | 51 | 47 | 55 | 50 |

| White Non-College | 39 | 44 | 42 | 40 | 37 | 37 |

Taken together, Arizona’s larger share of voters aged 65 and older and its lower Democratic support levels among white college voters contribute to the state’s continued battleground status, with a recent history of electing both Republicans and Democrats in close statewide elections.

Urbanity and Rapid Population Growth

Rapid population growth in Arizona is causing the state to become less rural, especially in and around Maricopa County, in which Phoenix and many of its suburbs are located. Comparing 5-year Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) estimates from 2008-2012 and 2017-2021, over this period Maricopa County’s CVAP increased by 21%, compared to 10% national-level population growth. 5Among the 128 US counties with estimated 2008-2012 populations of at least 500,000, Maricopa County experienced the 15th highest percent increase in CVAP between 2008-2012 and 2017-2021, putting it in the top 15% of these counties in terms of CVAP growth.

Table 4. Rapid Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) Growth in Maricopa County

| 2008-2012 CVAP | 2017-2021 CVAP | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maricopa County, AZ | 2.5M | 3.0M | 21% |

| United States | 215M | 236M | 10% |

This growth has contributed to Arizona’s electorate becoming more suburban and less rural than the national average. In 2022, 65% of Arizona’s voters were categorized as suburban, compared to 59% nationally. By contrast, 15% of Arizona’s voters were categorized as rural, compared to 23% nationally.

Figure 6. Composition of the Arizona and National Electorates by Urbanity, 2022

More population-dense areas are generally more Democratic-leaning, a trend that has grown for the past several election cycles.

Table 5. Democratic Support among Arizona Voters by Urbanity

| Arizona | National | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 Pres | 2016 Pres | 2020 Pres | 2022 House | 2012 to 2022 | 2012 Pres | 2016 Pres | 2020 Pres | 2022 House | 2012 to 2022 | |

| Rural | 43 | 41 | 42 | 40 | -3 | 39 | 32 | 33 | 30 | -9 |

| Suburban | 44 | 47 | 49 | 47 | +3 | 51 | 51 | 54 | 50 | -1 |

| Urban | 54 | 58 | 60 | 60 | +6 | 72 | 74 | 72 | 71 | -1 |

Down-Ballot Support

In Arizona, down-ballot House races saw lower two-way Democratic support shares than statewide Gubernatorial and Senate races. Arizona also saw Democratic support declines from Senator Mark Kelly to Governor Katie Hobbs. Ticket splitting — voting for different party’s candidates for different offices — likely explains these small, but substantively important differences in support.

Drop-offs in Democratic support between the Senate and Gubernatorial races were more visible among different constituency groups than drop-offs in Democratic support between statewide and House races. Senator Kelly received a greater Democratic support share than Governor Hobbs from attracting higher support among Latino, Black, and younger voters. Meanwhile, statewide candidates received greater Democratic support shares than their House counterparts because of higher support shares among white voters (especially white college voters, white suburban voters, and white women voters) and older voters in the Baby Boomer, Silent, and Greatest generations.

Michigan

Michigan was part of the “Blue Wall” that fell to Trump in 2016, causing Democratic campaigns to reinvest in the state. In the ensuing years, Democratic candidates have won significant victories by building and retaining a multi-racial, multi-class coalition. Michigan Democrats secured trifecta control of the governor’s office and both houses of the state legislature while statewide Democratic elected officials, including Governor Gretchen Whitmer, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, and Attorney General Dana Nessel have taken on national prominence. Additionally, Senator Gary Peters successfully led Democrats’ efforts to expand their Senate majority.

The state’s history as a union stronghold also looms large. Michigan is the 11th most union-dense state and in 2022, with 14% of workers being union members. Additionally, Democrats overturned the state’s so-called “right to work” anti-union law. Heading into 2024, the revitalized United Auto Workers are striking against the Big 3 automakers and enjoying explicit support from Democratic office-holders, including President Biden, who joined them on the picket line.

Race

Michigan’s electorate is less racially diverse than the country as a whole. White voters comprised 84% of the Michigan electorate in the 2022 midterms, compared to 76% nationally. In this same year, Black voters made up 10% of the electorate both in Michigan and nationally. Latino, AAPI, and voters of other racial groups make up a smaller fraction of the electorate, which makes estimates of support levels of other voting trends more difficult and uncertain at the state level.

Figure 7. Composition of the Michigan and National Electorates by Race, 2022

Black Voters

In Michigan, the Black share of the electorate decreased slightly from 11% in 2018 to 10% in 2022. Over this same period, the Black share of the national electorate declined from 12% to 10%, suggesting that trends in Michigan followed the broader pattern of drop-off in turnout among voters of color seen in many states between the 2018 high turnout, “blue wave” election and the 2022 midterms.

Black voters’ two-way Democratic support shares also steadily decreased from their remarkably high levels between the 2016 Presidential election, 2020 Presidential election, and 2022 midterms. Both in Michigan and nationally, Black voters’ support shares declined from 94% support for the Clinton/Kaine ticket in 2016 to 88% support for Democratic House candidates in 2022. Declines in Democratic support among Black voters in Michigan parallel shifts among Black voters nationally, although despite these decreases Black voters continue to support Democratic candidates at very high rates. However, declines in Black Michigan voters’ Democratic support contrast with overall shifts in Michigan, where two-way Democratic support increased or remained stable – albeit from much lower levels – between the 2016 Presidential and 2022 midterm elections.

Table 6. Vote Share and Democratic Support among Black Voters in Michigan, All Voters in Michigan, and Black Voters Nationally

| Percent of Voters | Dem Support (Two-Way) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2022 | 2016 Pres | 2020 Pres | 2022 Gov | 2022 House | |

| Michigan Black | 11 | 10 | 94 | 92 | 91 | 88 |

| Michigan Total | -- | -- | 50 | 51 | 56 | 51 |

| National Black | 12 | 10 | 94 | 91 | -- | 88 |

White Voters

White voters have become increasingly polarized based on education levels, with white voters without four-year college degrees moving toward Republicans in recent cycles and white voters with four-year college degrees moving toward Democrats. In the Rust Belt, in particular, Democrats lost substantial support among white non-college voters between the 2012 and 2016 Presidential elections.

Figure 8. Democratic Support among White College and Non-College Voters in Michigan and Nationally, 2012-2022

In 2020, however, the Biden/Harris ticket saw steady support among Michigan’s white non-college voters and increased support among its white college voters relative to 2016. In 2022 House contests, white non-college voters swung toward Democrats while Democratic support among white college voters decreased, reducing the amount of education polarization in the white electorate.

Governor Gretchen Whitmer overperformed House Democrats, increasing two-way Democratic support by 2 percentage points to 59% among white college voters and 8 percentage points among white non-college voters to 47% compared to Biden/Harris 2020 support levels.

Table 7. Democratic Support Shifts among White College and White Non-College Voters, 2020-2022

| Michigan | National | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 Pres | 2022 Gov | 2022 House | 2020 Pres | 2022 House | |

| White College | 57 | 59 | 52 | 55 | 50 |

| White Non-College | 39 | 47 | 43 | 37 | 37 |

Urbanity

Urbanity and higher population density are associated with higher Democratic support. One factor that makes Michigan more competitive than similar states is that it is more suburban and rural than the country as a whole. In 2022, 10% of Michigan voters were categorized as urban, compared to 19% of voters nationally. By contrast, 62% of Michigan voters were categorized as suburban compared to 56% nationally, and 28% of Michigan voters were categorized as rural compared to 25% nationally.

Figure 9. Composition of the Michigan and National Electorates by Urbanity, 2022

Age

Younger voters are generally more Democratic-leaning, a trend that has not always been true but is increasingly evident in recent election cycles. The youth vote in Michigan is worth examining in depth, especially because of recent changes to state voter registration law that have dramatically increased youth registration and turnout.

Overall, states with highly contested elections saw young voters rival their 2018 turnout, helping drive Democratic victories. Michigan, in particular, is among just 4 states that saw increases in turnout above and beyond 2018, according to CIRCLE at Tufts University.6CIRCLE’s analysis combines Catalist vote history and age data with Census estimates of the citizen voting age population (CVAP). The other three states were Arkansas, New York and Pennsylvania. Among those states, Michigan was the only one with a high profile statewide race in 2018, making the turnout increase above 2018 even more remarkable.

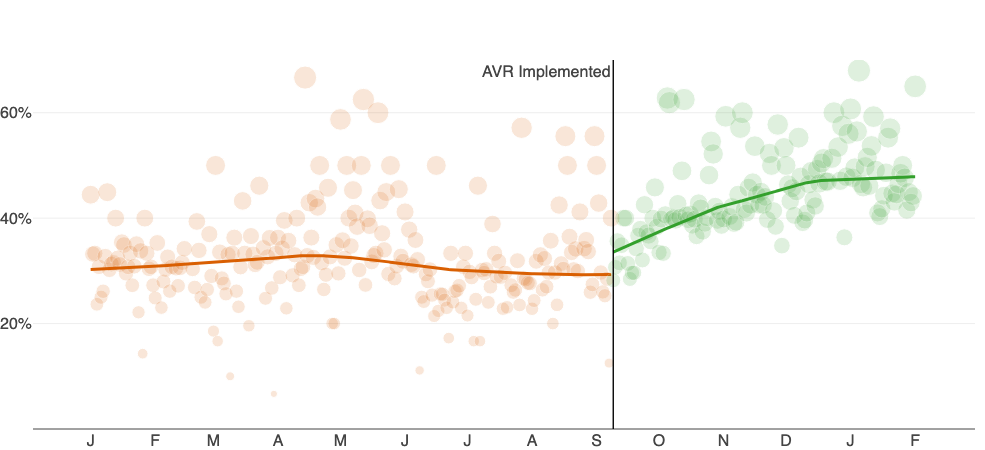

Youth voter registration in Michigan has increased since 2019, following Michigan’s implementation of Automatic Voter Registration (AVR), which allows eligible Michigan residents to register when they interact with the Department of Motor Vehicles. Because Michigan did not hold any statewide general elections in 2019, we can analyze how AVR increased registration among 18-24-year-old potential voters, who were otherwise not exposed to any significant campaign messaging or spending.

Figure 10. New Voter Registrations in Michigan among 18-24-Year-Olds around the Implementation of AVR

Between the 38-month periods preceding and following the introduction of AVR, the share of new registrations composed of 18-24-year-olds increased from 17% to 41%, a 24 percentage point increase. The number of new registrations among 18-24-year-olds also more than doubled between these two periods, from 175,000 in the 38 months preceding AVR to 497,000 in the 38 months between the introduction of AVR and the 2022 midterms.

Largely because of growth in the number of 18-24-year-old new registrants, the overall number of new registrants increased slightly from 1.1 million in the 38 months preceding the implementation of AVR to 1.2 million in the 38 months following this policy change. However, increases in the number and share of 18-24-year-old new registrants were partially offset by decreases in the number and share of 25-64-year-old new registrants. Meanwhile, registrations among voters aged 65 and up remained stable in percentage terms and increased in absolute terms across these two periods.

Table 8. Composition of New Registrants by Age Cohort in Michigan, 2016-2022

| 2016-2019 | 2019-2022 | Difference (K) | Difference (pp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 17% (175K) | 41% (497K) | +322K | +24pp |

| 25-29 | 24% (256K) | 16% (193K) | -63K | -8pp |

| 30-39 | 26% (276K) | 16% (194K) | -82K | -10pp |

| 40-49 | 12% (126K) | 8% (95K) | -31K | -4pp |

| 50-64 | 13% (136K) | 10% (126K) | -10K | -3pp |

| 65+ | 8% (89K) | 9% (104K) | +15K | +1pp |

| Total | 1.06M | 1.21M | +150K | -- |

Abortion on the Ballot

In November 2022, the majority of Michigan voters approved Proposal 3, the “Right to Reproductive Freedom Initiative,'' which codified reproductive rights within the state, including the right to an abortion. We might expect that the presence of this measure on the 2022 midterm ballot would drive turnout among women and young voters. As highlighted in Catalist’s national 2022 What Happened report as well as its Women constituency report, multiple lines of evidence underscore the degree to which abortion was a mobilizing issue for women — especially young women — in 2022.

However, there are often disconnects between how people vote on ballot initiatives and where parties and candidates stand on ballot questions. In Michigan, voters approved Proposal 3 with 57% of the vote. Meanwhile, Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer was re-elected by a double-digit margin of over 10 points, (winning 55% of the two-party vote), raising the question of where support differences emerged between Proposal 3 and the gubernatorial race.

Following Republican appointees on the Supreme Court overturning long-standing abortion rights in Dobbs, Catalist’s overall What Happened report and Women’s Constituency Report show sustained spikes in registration shares among women and young voters. Building on this trend, we expected to find higher support shares among women and young voters for Proposal 3 than for Governor Whitmer. We did not find these differences, though women and young voters did support both Proposal 3 and Governor Whitmer at higher rates.

Drawing on surveys fielded in Michigan and precinct-level demographic data, we instead found differences in support for Proposal 3 and Governor Whitmer by party identification, race, and marital status. Support for Proposal 3 was divided less clearly along party identification lines than support for Whitmer. Self-identified Democrats supported Whitmer at higher rates than Proposal 3, with support shares of 97% and 89% respectively. Meanwhile, 17% of self-identified Republicans supported Proposal 3 while only 4% of self-identified Republicans supported Whitmer, suggesting Republican-leaning voters are more moveable on specific ballot questions than they are for candidates. Differences in support within each party are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

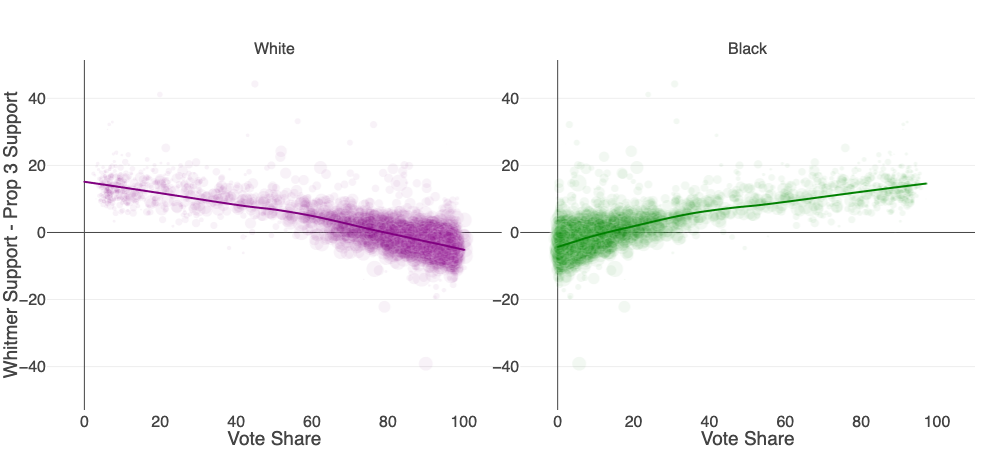

Figure 11. Differences in Support for Whitmer and Proposal 3 by Party Identification

There were also differences in support for Governor Whitmer and Proposal 3 among white and especially among Black voters. White voters supported Governor Whitmer at lower rates than they supported Proposal 3 – with support shares of 45% and 50% respectively – though these differences are not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. By contrast, Black voters expressed substantially higher levels of support for Governor Whitmer relative to Proposal 3, with support shares of 82% and 69% respectively. This 13 percentage point difference in support among Black voters is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

Figure 12. Differences in Support for Whitmer and Proposal 3 by Race

Precinct-level analyses further substantiate these differences by race. There is a negative relationship between a precinct’s white vote share and the difference between its support for Governor Whitmer and Proposal 3, suggesting that precincts with higher concentrations of white voters supported Proposal 3 at higher levels than they supported Governor Whitmer. By contrast, there is a positive relationship between a precinct’s Black vote share and the difference between its support for Governor Whitmer and Proposal 3, meaning that precincts with higher concentrations of Black voters supported Governor Whitmer at higher rates than Proposal 3.

Figure 13. Differences in Support for Whitmer and Proposal 3 by White and Black Population Density

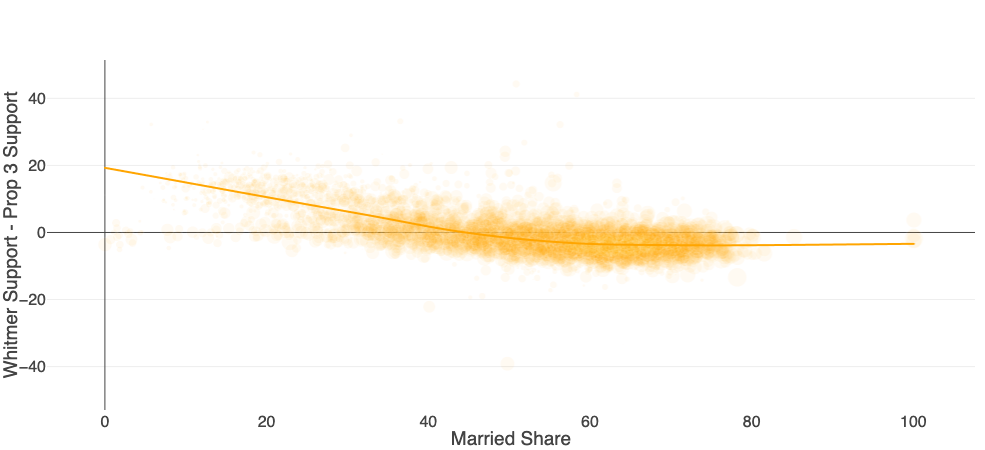

Finally, precinct-level analyses show differences in support for Whitmer and Proposal 3 by marital status. There is a negative relationship between a precinct’s share of married voters and the difference between its support for Governor Whitmer and Proposal 3. This suggests that precincts with smaller shares of married voters supported Governor Whitmer at higher rates than they supported Proposal 3, and conversely, precincts with larger shares of married voters supported Governor Whitmer at slightly lower rates than they supported Proposal 3.

Figure 14. Differences in Support for Whitmer and Proposal 3 by Marital Status

Down-Ballot Support

In Michigan in 2022, down-ballot House races saw lower two-way Democratic support shares than statewide Gubernatorial and Senate races. Governor Whitmer also received higher Democratic support shares than House candidates among older voters in the Baby Boomer, Silent, and Greatest generations, women voters (especially married women and white women), married voters, rural and suburban voters, and voters with 4-year college degrees.

Winning Coalitions, Differing Lines of Evidence

The last two presidential elections have been remarkably close, with margins of victory consisting of just a few thousand voters in a handful of swing states, despite larger Democratic leads in the national popular vote. These narrow victories underscore the value of every part of an electoral coalition in battleground states, including traditional “swing voters” who cast ballots for different party candidates over time as well as “mobilization” audiences who lean Democratic but may not vote in every election, although the dividing lines between these types of audiences are not cut-and-dry in theory or practice.

Below, we discuss different types of individual-level voting patterns and the degree to which voter files, surveys, and other tools can help us analyze their potential contribution to a winning coalition. These questions are complex and campaign strategies involve significant assumptions and value judgments that campaigns must ultimately make in a competitive environment as they process live data. We urge readers to exercise skepticism whenever they see claims that any single group is the “key” to winning or losing an election and to resist viewing outreach to any group of potential voters as a 1:1 tradeoff against outreach to another group.

Base Voters — So-called “base” voters reliably vote for Democrats or Republicans in subsequent general elections, including midterms. Base voters are well-represented in voter files because they frequently interact with the electoral system. However, campaigns and candidates can’t take base voters for granted. For instance, some base voters may drop off in low turnout years while others may become ticket splitters or swing voters, casting their first ballots for the opposing party. Additionally, millions of new voters enter the electorate each year and millions more move to new states, complicating analysis of who might constitute a “base voter.”

First-Time Voters — Some portion of people who have not participated in previous elections cast their first ballots each election cycle. These voters are largely young people who have turned 18 since the last presidential or midterm election. However, some first-time voters have gone through multiple election cycles without casting a ballot before deciding to participate in an election. Because these voters have never interacted with campaigns or voter file systems before, their behavior is difficult to predict. While young voters have increasingly leaned toward Democrats in recent campaigns, other non-voters don’t lean particularly strongly toward either party when surveyed.

Surge Voters — Surge voters tend to cast ballots in high-turnout presidential election years but are more likely to skip midterms and odd-year elections. Some surge voters may only engage in very high-salience elections. The number of “surge” voters has declined in recent years as voters have smashed turnout records, including Democratic voters who cast ballots in 2018 at presidential turnout levels and the Democratic and Republican voters who set turnout records in 2020. Potential “surge” voters are often a priority for presidential campaigns, which seek to identify likely supporters who may be on the fence about updating their registration information or casting ballots. Importantly, these voters may require what has been traditionally defined as mobilization (encouragement to vote) as well as persuasion (being presented with arguments about who to vote for). Generally, these approaches are combined as forms of engagement for specific audiences across campaign cycles.

Swing Voters — Swing voting is a general term that can encompass many types of voting behavior, discussed below, including switching party voting patterns, ticket splitting, and undervoting and rolloff.

Switching Party Voting Patterns — Each election cycle, a small fraction of self-identified Republicans will cast ballots for Democrats or vice-versa. For instance, according to the Pew Research Center’s voter-file-verified surveys, approximately 4 percent of self-identified Republicans voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 while 5 percent of self-identified Democrats voted for Donald Trump. In 2020, these survey results flipped, with 4 percent of self-identified Democrats voting for Trump and 5 percent of self-identified Republicans voting for Joe Biden. However, these findings are not the whole story. For instance, some Republican voters who cast ballots for Mitt Romney in 2012 and Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden in subsequent presidential elections may have stopped identifying themselves as Republicans to pollsters, instead switching to Independent or Democratic. Further, attempts to repeatedly survey the same people over time are complicated by the fact that stronger partisans are more likely to stay in such surveys. At the same time, traditional methods of identifying voters based on their formal party affiliation have two major limits. First, only 31 states and Washington, DC have partisan registration. Second, more people are registering and identifying as Independents, including people who nevertheless consistently vote for just one party. So while we know that these types of “swing voters” can play a decisive role in campaigns, they can not be singularly identified or differentiated from other groups of voters.

Ticket Splitters — Ticket splitters may cast ballots for candidates of either party. According to Catalist survey data, roughly 15% of voters say they vote for Democrats and Republicans in equal amounts. Frustratingly for campaigners, these voters are difficult to identify in the aggregate or individually because less partisan voters tend to interact less with campaigns and voter files. Additionally, the nature of secret ballots makes it very difficult to analyze how much of a given margin of victory consists of ticket splitters. However, in some states, election administrators publish anonymized completed ballots, which allows researchers to precisely estimate the fraction of an outcome that can be attributed to various types of voting behavior, including undervoting, roll-off, and ticket-splitting.7See, for instance, The Swing Voter Paradox: Electoral Politics in a Nationalized Era. Shiro Kuriwaki, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Undervotes— Undervoting refers to skipping top-of-ticket races. Undervotes are usually studied by election administrators as a measure of how effectively ballots and machines are designed, but in 2016, rates of undervoting were particularly high, at 1.4 percent, likely the result of protest votes against Clinton and Trump.

Rolloff — Rolloff refers to the tendency for voters to refrain from casting ballots the further they get down the ballot. This is why presidential and other top-of-ticket races consistently show higher vote totals than House races and state legislative races.

Different Models Show Different Paths to Victory

Below, we analyze the vote totals in Arizona and Michigan using different methods to illustrate the difficulty of coherently identifying the combinations of turnout and partisan voting patterns that yielded a winning coalition for Democrats.

In reality, the actual electorate in any highly contested election is likely comprised of a combination of base voters, new voters, vote switchers, ticket splitters, undervoters, and roll-off voters while parties also attempt to limit dropoff among consistent partisan voters from presidential to midterm years. However, we can use voter file data, polling, and other sources to estimate likely upper and lower bounds of how much differential turnout among strong partisans and various types of swing-voting behavior may have contributed to a specific outcome. In this memo, we present a few approaches to doing this, though it is not exhaustive in the least.8Our analysis is consistent with other public post-election research using voter files to verify if survey respondents actually voted. Importantly, other analyses tend to focus on the national popular vote in House races, which is consistent with historical analyses of midterm electorates. However, Catalist’s 2022 analysis found significant differences among House race electorates and statewide electorates in states with highly contested elections, leading us to split our analysis to illustrate the differences in-depth. First, a December 2022 analysis from Nate Cohn of the New York Times found that registered Republicans and likely Republican voters were more likely to turn out than their Democratic counterparts in Georgia and Arizona, but that Democrats ultimately prevailed. This suggests significant levels of swing voting behavior among Republican voters in those races, but this conclusion is complicated by a few factors, including the role partisan-leaning independents play and voters who have switched their partisan voting patterns but not their registration. The second is the Pew Research Center’s biennial survey of the general electorate, which was published in July of 2023. They found a Republican turnout advantage, with 67% of 2020 Biden voters casting ballots in 2022 and 71% of 2020 Trump voters turning out in 2022. At the same time, they found 7 percent of 2020 Biden voters who cast 2022 ballots voted for Republican House candidates while only 3 percent of 2020 Trump voters who voted in 2022 cast ballots for Democratic House candidates. These findings suggest that Republicans lost in many races despite a relative turnout advantage, against suggesting swing voting played a significant role in many statewide Democratic victories, which also benefited from relatively higher Democratic turnout for a midterm election. Finally, another analysis from the New York Times and Cohn, published in July 2023 with more voter file data available found that 73% of registered Republicans turned out in 2022 compared to 63% of registered Democrats. Similar to the Pew study, Cohn found that 69.1 percent of 2020 Trump voters turned out in 2022 compared with 66.7 percent of 2020 Biden voters. These figures suggest that turnout alone would have resulted in significant Republican victories, pointing to a combined role for turnout and swing voting to explain actual election outcomes. These trends are different in states with highly contested statewide elections. Cohn finds the Democratic turnout was relatively higher in Michigan and Pennsylvania, where Democrats enjoyed significant wins. Some top-of-ticket candidates, such as Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in Michigan and Gov. Josh Shapiro in Pennsylvania, performed even better, suggesting a combined role of higher Democratic turnout and swing voting behavior.

Here we show three different methods for breaking down the 2022 electorate:

- An aggregation of our voter file model of the likelihood of supporting Joe Biden in the 2020 election. This is the same model that powered our What Happened 2020 report, what we call the “Biden support model”. This approach uses 2020 Biden support levels to estimate the fraction of the 2022 electorate in each state that supported Biden in 2020.

- A combination of the Biden support model and 2022 survey data Catalist has compiled from multiple firms and across multiple modes from live phone calls to cellphones and landlines, text messages, and online panel interviews, all matched to the Catalist voter file.

- The same method was used in Approach 2 (above) but with adjustments by mode and the firm that collected the data, similar to the house effect calculations poll aggregators perform before presenting a polling average. We explored this third approach after observing that the results that we got in Approach 2 were different after subsetting the sample to different sources of survey data as well as the inclusion of different variables in statistical models we ran to quantify the level of support for Joe Biden in 2022.

Each method is consistent with real-world results given the small margins we are examining, however, single-point differences can lead analysts to different logical conclusions about the 2022 electorate.

First, we know that in 2020, the Biden / Harris ticket received 52% of the national popular vote. Meanwhile, in 2022, Democratic House candidates received 49% of the vote. This 3% difference is small but was decisive in many races. Using these methods, we can estimate what fraction of the 2022 electorate were likely Biden voters in 2020. Some methods yield an answer of 49%, meaning Democrats’ entire 2022 coalition could have been composed of likely Biden voters from 2020, with midterm year turnout dropoffs explaining the 3% difference between Democratic support in each cycle.

Other methods yield a slightly different answer, finding that 50% of the 2022 electorate were likely Biden voters in 2020. This one-point difference leads to a different logical conclusion, with turnout differences between each party’s 2020 voters alone insufficiently explaining Democrats’ 49% vote share nationally. In this case, at least one-third of the difference would have been made up of the 2020 Biden voters who turned out in 2022 and cast ballots for House Republicans.

The story is even more complicated when we examine statewide races. In Arizona, Senator Mark Kelly’s 2022 performance improved on Joe Biden’s 50% by 2 points, netting him 52% of the two-party vote, whereas Governor Katie Hobbs garnered the same 50% that Biden received 2 years earlier. Meanwhile, House Democrats performed 2 points worse than Biden’s 2020 vote share with 48% of the two-party vote.

Table 9. Comparing Survey Data and Election Results in Arizona, Michigan, and Nationally

| Biden/Harris Performance ('22 Voters) | 2020/2022 Election Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography | Voter File Only | Voter File + Polling #1 | Voter File + Polling #2 | Biden/ Harris | Senate | Governor | US House |

| AZ | 48% | 50% | 48% | 50% | 52% | 50% | 48% |

| MI | 50% | 50% | 52% | 51% | -- | 55% | 51% |

| US | 50% | 49% | 50% | 52% | -- | -- | 49% |

In the three scenarios estimating the fraction of each candidate’s coalition composed of Biden 2020 voters, we find that they vary from 48% to 50% of the midterm electorate. This means that Senator Kelly likely won over 2 to 4 percent of midterm voters who cast ballots for Trump in 2020 while Governor Hobbs's performance could have involved some small amount of Republican vote switching or have been solely a function of Democratic turnout dropping off in a midterm year. Further, the House results could be explained by differing turnout among consistent Democratic and Republican voters at one end or 2 percent of likely 2020 Biden midterm voters casting ballots for Republican House candidates at the other.

The results for Michigan are similar. Approximately 50 to 52% of the electorate were likely 2020 Biden voters, while Whitmer secured 55% of the vote. Therefore, Whitmer’s coalition (compared to Joe Biden’s in 2020) could have involved some higher turnout for Democrats in her race as well as winning over 3 to 5 percent of likely 2020 Trump voters who cast 2022 ballots. Finally, House candidates' performance ranges from winning over 1 percent of 2020 Trump voters who cast midterm ballots to losing a percentage point of Democratic turnout.

While it can be frustrating for analysis to yield conflicting lines of evidence, we feel it’s important to illustrate the limits of these methods and the necessity of operating campaigns in the face of uncertainty. We urge readers to resist easy or simplistic explanations about the electorate and to carefully consider how campaigns can build winning coalitions in a complex, highly competitive environment.

What Happened 2022 Constituency Reports

Contributors

Lead authors. Kirsten Walters, Data Scientist; Jonathan Robinson, Director of Research

Project lead. Hillary Anderson, Director of Analytics; Haris Aqeel, Senior Advisor

Editor. Aaron Huertas, Communications Director

Graphics and data engineering. Kirsten Walters, Data Scientist

Catalist Executives. Michael Frias, CEO; Molly Norton, Chief Client Officer

Catalist Data Team. Russ Rampersad, Chief Data Officer; Lauren O’Brien, Deputy Chief Data Officer; Dan Buttrey, Director of Data Acquisition

Many current and former staff members have also contributed to this report through their work building and maintaining the Catalist file. These insights would not be possible with the long-term investment Catalist has made in people and data since 2006. We also thank our partners who have provided valuable insights throughout our development of the 2022 What Happened series.

What Happened™ Catalist © LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Proprietary data and analysis not for reproduction or republication.

Catalist’s actual providing of products and services shall be pursuant to the terms and conditions of a mutually executed Catalist Data License and Services Agreement.