Lead Author: Justine D'Elia-Kueper, Senior Data Scientist

Coauthor: Yair Ghitza, Chief Scientist

Democrats are facing electoral headwinds as the midterms heat up — which we expect when one party controls the presidency and both chambers of Congress — but are changes to party registration something they should worry about?

An AP analysis published Monday carried the headline that “More than 1 Million Voters Switch to GOP in Warning for Dems.” Given the beneficial nature of this statement for the Republican Party, Texas governor Greg Abbott and Florida Senator Rick Scott predictably tweeted out the story with enthusiasm.

But when we analyzed this assertion against Catalist’s voter registration database — the longest-running voter file outside the two major parties — we reached a different conclusion. In fact, we found that registered Republicans and Democrats “defected” from their party at the same rate since the 2020 election.

Understanding Claims About Voter Registration

Conclusive assertions about the electorate need to be supported by a careful analysis of data. To this end, while the AP headline suggests that more than 1 million people affirmatively switched their party registration from Republican to Democrat, the underlying article caveats this claim. Therefore, the conclusion reached by the article warrants closer review. Moreover, our own analysis of the Catalist voter file suggests that the story is much more nuanced than as reflected within the article.

As stated in the article, the AP analyzed voter file data provided by the data firm L2. Voter file data in its simplest form lists registered voters and associated public information they provide to election offices. Because voter registration in the United States is handled at the state level there is no national list of registered voters. Instead parties and firms compile voter files across jurisdictions. In 31 states and Washington, DC, voters can explicitly choose to register with a political party. This is typically referenced as party registration. In other states, however, this information is not collected. To fill in these gaps, data firms like Catalist and L2 use statistical modeling to estimate people’s partisan preferences. We refer to this as partisan modeling. Partisan modeling can be extremely helpful, but it is not as concrete as party registration, which is based on individual-level decisions on voter registration forms. Modeling, by contrast, is highly dependent on polling and analytic decisions related to demographics, geography and prior election results, along with many other factors. Therefore, it is certainly possible (and in our view, likely) that partisan modeling would suggest differences over time that are not necessarily seen in the raw registration data.

“Defection” Rates Are Similar for Both Parties, Both Now and in 2018

The underlying text of the AP article makes it clear that the analysis is based on both changes in actual party registration and changes in L2’s partisan modeling. It is theoretically possible that both datasets would show a consistent move away from one party, however, that is not what we see on the Catalist voter file.

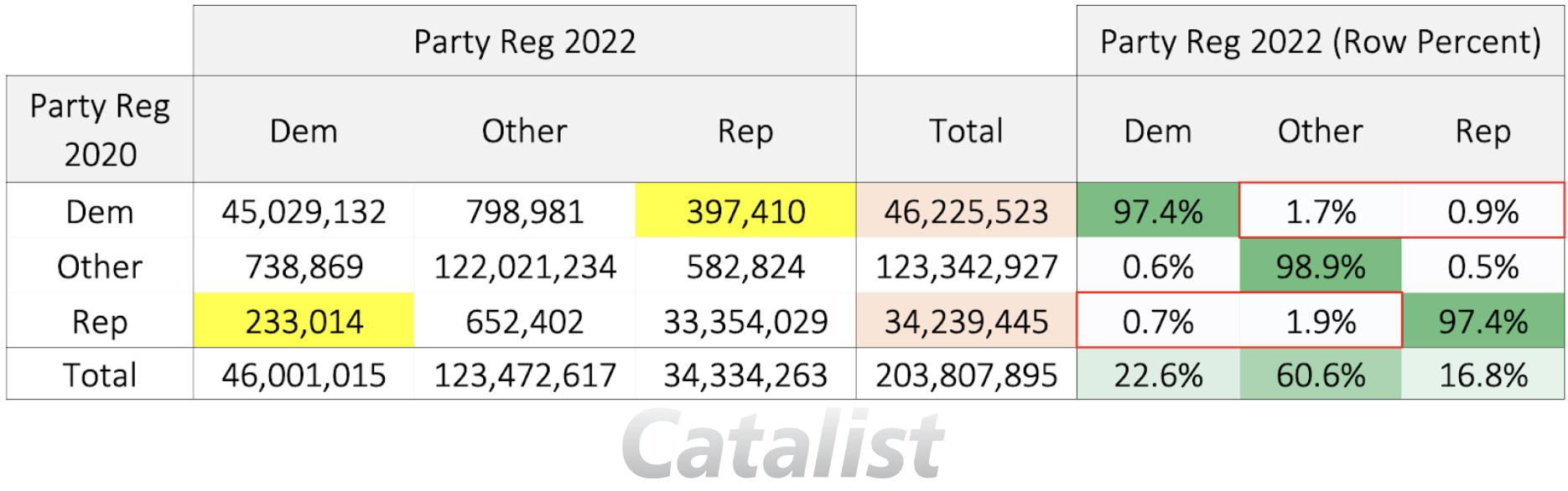

Because we maintain historical records, we are able to compare how party registration has changed among individuals who were registered to vote in both 2020 and today. These figures are presented in Table 1. For simplicity, we collapse minor party registrants, independents, and those who lack any party registration into a group labeled Other.

Overall, we see that there are 46 million registered Democratic voters and 34 million registered Republicans. The majority of registered voters — 123 million people — have no party affiliation on file.

According to the Catalist voter file, since the 2020 election:

- 2.6% of Democratic registrants have “defected,” with 0.9% switching to a Republican registration, and 1.7% switching to Other.

- The exact same percentage – 2.6% – of Republican registrants also defected, with 0.7% switching to Democratic, and 1.9% switching to Other.

To be clear, there are more Democratic-to-Republican party registration switches in raw numbers, but this is because there are more registered Democrats to begin with. The same percent of Democratic and Republican voters “defected” away from their party – 2.6% in each case, with 97.4% staying consistent.

Nothing in this data suggests that Democrats are suffering from a disproportionate amount of party switching. The absence of this finding in the party registration data suggests to us that the bulk of the changes reported on by the AP are a product of L2's partisan modeling.

Table 1: Party registration changes, from 2020 to 20221In each state, we compared the first acquired voter file from after the 2020 election to the most recent voter file. The first post-2020 voter file is the version that is most likely to have all of the people who voted in the 2020 election, including new registrants from that cycle. We also repeated this analysis using the 21 states where more than 50% of registered voters have a Democrat or Republican party registration. The substantive results are the same in either case.

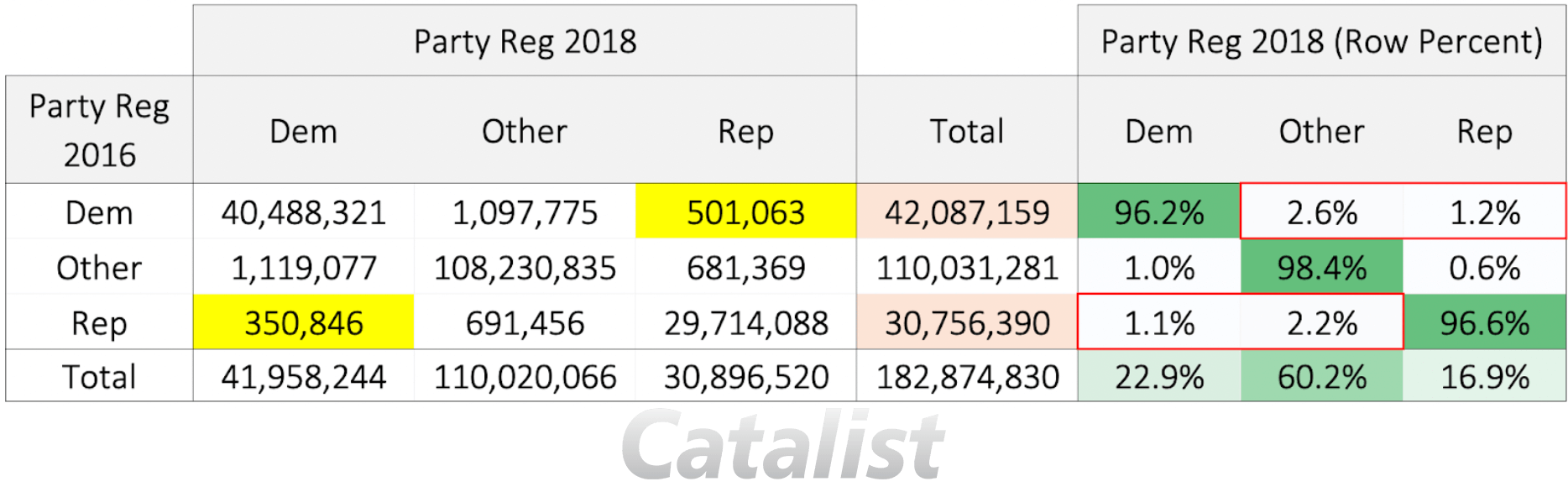

Table 2: Party registration changes, from 2016 to 20182This compares the first acquired voter file from after the 2016 and 2018 elections, in each state.

As an additional comparison point, we also examined defection rates from 2016 to 2018, which was a much more favorable environment for Democrats. There, we saw a similar pattern, shown in Table 2. This covers a full midterm election cycle and therefore includes slightly more defections overall, as the time period is longer.

In these years, the overall defection rates for Democrats and Republicans was 3.8% and 3.3%, respectively. From our perspective, the point is that these numbers are close to one another, and not that the Democratic rate was slightly higher (which can be due to a number of factors). In raw number terms, there were more Democratic defections, again because Democrats had a much higher number of registered voters to start with. Given Democrat’s success in the 2018 elections and the similarity in trends between this data and the current data, we do not find anything in this analysis that would support the conclusion that current changes in voter registrations should be a worrying sign for Democrats.

Conclusion

While the recent AP article prompted us to undertake this specific analysis, every recent election cycle has included media coverage of party registration data and modeling presented as bad news for Democrats. In 2016, Catalist collaborated with the New York Times to analyze these claims more generally. This type of analysis is difficult and partisan registration is declining for a variety of reasons. In some cases, such as purges of the voter rolls, there is a disproportionate effect on Democratic voters. But these trends appear to be unrelated to overall support for Democrats in the electorate. Other factors, such as party switching, may also be of lesser significance than they seem at first blush, since changes in party registration tend to follow rather than precede changes in actual voting behavior.

Since winning control of the presidency and both chambers of Congress in 2020, Democrats have faced the type of fundamental backlash we often see against incumbent parties in election years. This includes the wave elections in 2010 and 2018, which both resulted in changes to party control of the House. We also saw these effects in the “odd year” statewide elections in Virginia and New Jersey. However, we find no evidence that the current changes in party registration should add to these worries. Additionally, we are only just starting to see how potential voters are reacting to the unprecedented decision by conservatives on the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade.

For more on what the electorate looks like from the perspective of the Catalist voter file, please see the What Happened series.