By Jonathan Robinson

Interactive Data Visualizations by Justine D'Elia-Kueper, Chase Stolworthy, and Sarah Grant. Edited by Aaron Huertas, Yair Ghitza, and Meg Schwenzfeier. Site design by Melissa Amarawardana.

We'd like to thank our partners whose insights and contributions have been invaluable in making sense of the 2020 election. Further, this report would not have been possible without the dedication of many on the Catalist team, whose hard work maintaining this national database is paramount to our ability to produce these reports.1We would like to particularly thank Molly Norton, Maggie Dart-Padover, Peter Casey, Sarah Grant, Alan Julson, Anna Thorson, Jesse Zlotoff, Andres Cremisini, Hersh Gupta, Matt Zetkulic, Anna Baringer, Russ Rampersad, Dan Buttrey, Marguerita ten Houten, Jordan Tessler, Mary Toole, John Kim, Erin Thomas, and Nicholas Petrone in particular for their many important contributions to this project.

Additionally, we thank Ola Topczewska, Julie Laliberte, Barry Burden, and Charles Franklin as well as other in-state experts in Wisconsin and Nevada who reviewed the early draft findings of this report and whose feedback was invaluable in producing these analyses.

Introduction

Joe Biden and Kamala Harris won the 2020 election with 52% of the two-party vote nationally, building a multi-racial coalition that brought millions of new voters into the electorate. But that winning coalition looks different in battleground states based on both the demographic composition of the states themselves as well as important differences in how campaigns and voter outreach organizations invest in and treat potential voters in battleground states.

Catalist’s national-level What Happened analysis for 2020 focuses on what we can glean from our voter file at the national level. But battleground states differ demographically and politically from the country as a whole. By supplementing our national analysis with reliable, state-level data we can shed light on these distinctions.

When comparing these results to our national What Happened analysis — and even comparing changes across years and groups — we caution readers that statistical analysis of smaller populations and subpopulations come with higher levels of uncertainty.2Because Catalist data relies on both voter files and polling data, it does not use traditional margin-of-error reporting that many public polls do. These considerations are discussed further in the national What Happened analysis.

These uncertainties are larger at the state level. Catalist’s approach is a pooled model, meaning estimates are derived from national models, granular election results, survey data in states, demographic modeling, and other building blocks.

In our analysis, we pay close attention to each states’ unique administrative data regimes, in particular the idiosyncrasies of different jurisdictions’ voter files.3Nevada, for instance, tracks a voter’s party affiliation in their voter file, along with other standard information such as age. Wisconsin, on the other hand, does not collect party affiliation data. Further, the state used to publicly report voters’ date of birth but stopped doing so several years ago. As a result, only about 60% of active registered Wisconsin voters in our database have state-provided information on age. In our case, that 60% comes from historical voter files and other administrative data sources, while another 25% comes from commercial sources and other states voter files (among other sources), and for the 15% where we have none of that information, we model this demographic information in much the same way that we model demographics such as race, education, and marital status that don’t show up in most voter files. Broadly, the less partisan information the voter file contains, the less precisely models can project election results and the more uncertain our estimates are. Readers should be mindful of these concerns as well as small sample sizes where estimates within and over time may be more volatile and less reliable than in national data.

Wisconsin

The race in Wisconsin was incredibly close. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris carried Wisconsin by just 0.6%, a margin of only 20,000 votes. By contrast, Donald Trump carried the state by 0.7% in 2016, with a margin of fewer than 23,000 votes. Wisconsin was ultimately the “tipping point” state for Democrats’ Electoral College victory, meaning that in a slightly closer election it would have very likely been the decisive state.4The tipping point state is defined as the first state that produces an Electoral College victory when states are ranked by the margin of victory in each state. In especially close elections, the tipping point state may ultimately be decisive, as Florida was in 2000. In 2016, the tipping point state was Pennsylvania.

Turnout and vote choice by race and education

Wisconsin’s electorate is whiter, has fewer residents with a four-year college degree, and is more rural than the rest of the country. At the same time, statewide races require building a multi-racial coalition, with Black voters contributing significantly to Democratic wins, providing enough votes to exceed the margin of victory.

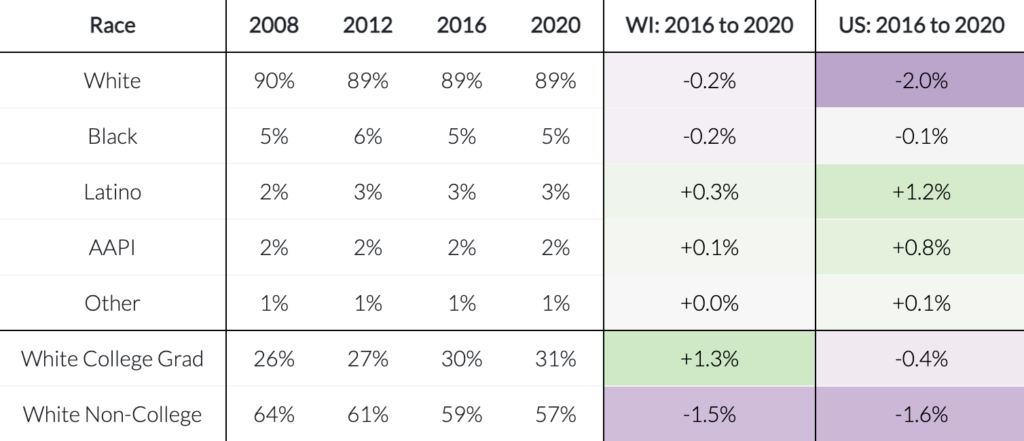

Wisconsin itself has become slightly more diverse in the past few years, though not as quickly as other states, especially among voters. In fact, looking at Table 1, the composition of the electorate in racial terms has stayed quite stable in Presidential elections going back to 2008.

Table 1: Wisconsin Electorate Composition by Race + Education

Figure 1: The Growing Education Divide Among White Voters in Wisconsin

Trends in vote choice, on the other hand, have changed quite a bit. As we can see in Figure 1, Barack Obama received 49% of the vote among white non-college voters in 2012, while in 2016, Hillary Clinton’s performance with that same demographic dropped 7 percentage points to 41%, and in 2020 stayed at around those levels for the Biden campaign. Meanwhile, Barack Obama received 53% of the white college-educated vote in 2012 while Hillary Clinton made large inroads with this group and won 57% of their votes. Joe Biden improved on Hillary Clinton’s performance, winning 61% of their votes.

Black voters key to winning coalition

Black voters provided overwhelming support for the Biden-Harris ticket, at 90% in two-way vote share, yielding a margin of approximately 125,000 votes for Democrats, far exceeding the margin of victory in the state.5This estimate comes from the results of our race and support modeling. Race is not self-reported in the Wisconsin voter file, as a result, we model it based on information drawn from voters' neighborhoods as well as their first and last names. First, we estimate what percentage of 2020 voters were Black, then we estimate what percent of those Black voters voted for Joe Biden compared to Donald Trump. We then multiply our estimates by the known numbers of votes cast across the state. This is merely an estimate and comes with some uncertainty, hence why we note “approximately” here as to not claim to have too much confidence in the exact numbers. While Black turnout increased by 1 point, turnout also increased more among other groups, causing Black voters’ share of the Wisconsin electorate to stay stable at around 5 percent. Nationally, Black turnout was up 5 points. The number of votes cast by Black voters increased in raw terms by 6.5% in Wisconsin but increased by about 14% nationwide.

At the same time, Democrats retained more of their high levels of support among Black voters in Wisconsin than in the rest of the country relative to 2016. Black support for the Democratic ticket fell by just 2 points in Wisconsin compared to 4 points nationally. These trends may be directly related. In our national report, we noted that the 2020 surge in Black voter turnout may have brought in less partisan first-time or infrequent voters, which reduced the overall margin for Democrats among an already very Democratic-leaning group. Wisconsin’s relatively lower boost in Black turnout could paradoxically have meant less change in overall Democratic vote share compared to other places with larger increases in Black voter turnout.

Education divides among white voters stand out

As in 2016, differences in support for Joe Biden among white voters along educational lines remained as an important divide in the 2020 election, though as we noted in the national report educational attainment is not the only way to capture class, wealth, or perceptions of one’s economic position. Many affluent small business owners did not attend college, for instance, while many highly educated teachers are underpaid compared to their college-educated peers.

We estimate that white non-college voters in Wisconsin are more Democratic than they are nationally by 2 to 3 percentage points, a function of the many so-called “ancestral Democrats” in the state. Compared to 2016, white non-college voters comprised 1 point less of the electorate, down to 58% of Wisconsin voters. Meanwhile, 40% of white non-college voters cast ballots for Joe Biden, a half-point drop in support for the Democratic ticket in Wisconsin since 2016. Nationwide, Biden and Harris gained 1 point with this group. At the same time, white college-educated voters increased their share of the electorate by 1 point compared to 2016, comprising 31% of all Wisconsin voters. They also voted strongly for the Biden/Harris ticket, with two-way support at 61%, a 4 point increase since 2016 compared to a 3 point increase nationally. White college-educated voters in Wisconsin were 7 percentage points more supportive of Joe Biden than similar voters nationally, relatively unchanged from 2016.

It’s also useful to think of this as a change in electoral coalitions. While white non-college voters remain a significant part of the Democratic coalition, their share dropped significantly in Wisconsin over the last three presidential elections. In 2012, Barack Obama's winning coalition in Wisconsin was 56% white non-college while in 2016, when Democrats lost the state, that number fell to 49%, a 7 point drop. And in 2020, Joe Biden's coalition was just 46% white non-college, a further 3 point drop from four years prior.

Young voters increased turnout and support for Democrats

Youth turnout is increasingly important for Democratic campaigns and 2020 presented unique challenges for helping young voters cast their ballots as work and campus life were heavily disrupted by the pandemic.

In most states, categorizing voters by age is straightforward since voters’ date or year of birth are almost always provided as a standard field on state voter files. In Wisconsin, however, the state collects age data to verify that voters are 18 or older but does not share the year or date of birth in their public voter file.

This data gap can present challenges for campaigns and youth vote organizations. Fortunately, through outside data acquisition and use of historical voter file data, Catalist can close this gap and only needs to model the year of birth of about 15% of Wisconsinites in our analysis. We do this using a combination of voter file data such as a voter’s registration date as well as other demographic information such as how first name popularity varies by birth year.

It is notoriously difficult to build this specific kind of demographic model because age is not missing at random on the voter file. As a result, we make many design and statistical adjustment choices in producing our age estimates in Wisconsin and these numbers have slightly more uncertainty.

According to our data, youth voter turnout in Wisconsin increased about as much as it did nationally, where higher engagement among young voters was the most significant driver of record-breaking turnout in 2020 to the 2016 presidential election. Nationally, the share of the electorate that was under 30 increased by a full percentage point, similar to what we see in Wisconsin. Looking at the percent increase in the number of votes among young voters in Wisconsin compared to the country as a whole, we get numbers of a similar magnitude: a 19% increase in Wisconsin versus about 22% nationwide.

This is true as well if we look at the year a voter was born, as we did in our national report. In both Wisconsin and the country as a whole, a greater proportion of voters were from younger age cohorts in 2020 than in 2016. However, we can see that changes in the generational composition of the Wisconsin electorate tell a slightly more nuanced story. Since we have access to the full enhanced voter file, we can examine specific cohorts for whom 2020 represented the second presidential election in which they could vote.6Since, as noted above, we rely more on modeling of age in Wisconsin than in other states, we are able to compare our findings to our own modeled estimates of youth voter turnout in Wisconsin based on the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration Supplement. In this case, we can validate our findings in Wisconsin on youth turnout in our estimates based on CPS data. The CPS data suggest the share of voters under the age of 30 stayed stable and that there was a percentage increase of about 15%. These kinds of comparisons highlight the importance of triangulating a variety of datasets to pull together a comprehensive picture of turnout, especially when there is substantial uncertainty as there is in the case of modeling age in the Wisconsin voter file. Our data show trends consistent with what the CPS estimates show, though to a different degree and magnitude. As a result, we encourage researchers to acknowledge discrepancies and differences to figure out for themselves how to evaluate the quality of the evidence at hand when making conclusions about the electorate.

The composition of the electorate based on year of birth, as we can see in Figure 2, as well as the changes from 2016 to 2020, are similar in Wisconsin as they are nationally, with younger voters increasing their share of the electorate. But this is particularly the case among the youngest cohorts in 2020. For example, voters born in 1998, who were 18 years old in 2016 (22 years old in 2020), almost doubled their share of the vote in 2020, from about .7% of 2016 voters to nearly 1.3% of 2020 voters. We also see some areas where trends in Wisconsin are different than nationally. For example, voters born in 1985 (who were 31 years old in 2016, 35 in 2020) saw large increases in their share of the vote compared to 2016 in Wisconsin, but not nationally. This could be a real trend in the data, or, as we note throughout this report and in footnotes, a function of our modeling strategy and process.

Figure 2: Composition of the Electorate by Generation, 2016-2020, WI & US

In Figure 3, we show that young voters—ages 18 to 29—saw a 2 point support increase for the Democratic ticket relative to 2016, representing a 3 point gain among younger white voters (56% to 59%) and an almost 6 point drop among young voters of color (though from relatively high support levels, 81% to 75%). The increases in support we see among white voters are likely the result of third-party voting dropping off in 2020, vote shifting, and the youngest voters in this cohort tilting more toward Democrats as older Millennials age out of this age group. The increases in support for Joe Biden among younger age cohorts in Wisconsin are in line with similarly sized increases we observed in our national report.7Since, as noted above, we rely more on modeling of age in Wisconsin than in other states, we are able to compare our findings to our own modeled estimates of youth voter turnout in Wisconsin based on the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration Supplement. In this case, we can validate our findings in Wisconsin on youth turnout in our estimates based on CPS data. The CPS data do suggest that youth turnout lagged national trends. For example, instead of falling, the CPS data suggest the share of voters under the age of 30 stayed stable and that there was a percentage increase of about 15%. These kinds of comparisons highlight the importance of triangulating a variety of datasets to pull together a comprehensive picture of turnout, especially when there is substantial uncertainty as there is in the case of modeling age in the Wisconsin voter file. Our data show trends consistent with what the CPS estimates show, though to a different degree and magnitude. As a result, we encourage researchers to acknowledge discrepancies/differences and figure out for themselves how to evaluate the quality of the evidence at hand when making conclusions about the electorate.

Figure 3: Young Democratic Support, 2008-2020

Women-led majority for Democrats, with increases in support from men

Since 2016, women voters in Wisconsin have continued to be an important source of votes for Democrats, offering 56% of their votes to Hillary Clinton (53% among White women and 83% among women of color). But, according to our data, Joe Biden actually lost ground among women in Wisconsin. This was true nationally, with Joe Biden receiving 55% of the vote from women voters in 2020, down one point from 2016. But this was even more true with women of color, whose support for Joe Biden dropped 6 points in two-way vote share to 77% (still a strong level of support for Democrats relative to men and white voters). Even with this drop, women are a much more Democratic-leaning group than men. In Table 2, we show that is the case, among white voters, across marital status and education groups. In fact, within all of these groups the gender gap, while still significant, fell from 2016 to 2020.

At the same time, men, in particular white men, shifted their support more toward Democrats in 2020, voting 41% for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and 45% for Joe Biden in 2020. Those trends held true across marital status and educational levels, as noted below, with the biggest increase in support coming from college-educated white men (6 points) and married white men (also 6 points). There has been some speculation as to why this is, with some hypotheses suggesting Joe Biden targeted his campaign appeals to voters in a way that would be particularly persuasive for men, while others suggest men may have been uniquely opposed to the first woman-led presidential ticket in 2016. At the same time, women had moved much more toward the Democratic Party between 2012 and 2016, potentially leading to ceiling effects on gains we might expect from women voters. The answer to these questions likely lies in surveys and other qualitative data that can speak to voters' motivations and underlying beliefs, which our data are unable to.

Table 2: Vote Choice for White Voters for Gender by Marital Status and Gender by Education

| White | 2016 | 2020 | 2016 to 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Men | 48% | 47% | -0.5% |

| Single Women | 63% | 59% | -4.0% |

| Married Men | 34% | 40% | +6.1% |

| Married Women | 46% | 47% | +1.0% |

| College Grad Men | 50% | 56% | +6.2% |

| College Grad Women | 63% | 65% | +1.9% |

| Non-College Men | 33% | 35% | +2.2% |

| Non-College Women | 48% | 45% | -2.9% |

Wisconsin’s political geography mirrored national trends

Figure 4: Change in Democratic Support in Wisconsin by Population Density

In 2020, Joe Biden’s support in urban areas declined compared to 2016, which follows from the relative concentration of voters of color in Wisconsin’s cities. In Figure 4, we sort precincts by population density along with the percentage change in Democratic vote share and the percentage change in voters of color from 2016 to 2020. This illustrates that Biden and Harris increased their support in suburban areas overall, while support in rural areas remained stable, even declining modestly in the most rural areas of the state. The growth in participation by voters of color in Wisconsin boosted some of Biden’s overperformance of Clinton in suburban areas of Wisconsin. This is due, in part, to those suburban areas being less Democratic overall compared to urban areas and the increased votes from voters of color in those areas being more Democratic than those of the existing population--whereas marginal voters in urban areas were less Democratic than the already existing urban voter base, leading to a decline in votes in those areas.

Wisconsin’s suburban areas are not growing as diverse as quickly as other states, such as Nevada. As a result, it is much more likely that changes in vote share in Wisconsin could be attributed to the Biden/Harris ticket making gains through conversion of third party or Republican voters from 2016. Other contributing factors, such as the in-migration of college-educated white voters, or a Democratic turnout advantage in these areas are also consistent with these data. By contrast, these latter factors likely played a bigger role nationally and in Sunbelt states like Nevada than it did in Wisconsin.

Down-ballot races varied

Democratic House candidates in 2020 generally under-performed the Biden-Harris ticket. This is due almost exclusively to ticket-splitting, in which voters cast ballots for candidates from both major parties rather than the much more common straight-ticket voting.

Nationally, voters of color and white college-educated voters supported Democratic U.S. House candidates at slightly higher rates than they supported Joe Biden. By contrast, white non-college voters supported Democratic House candidates at a rate of 3 points lower than the presidential ticket.

To help understand how down-ballot races differed from the top-of-the-ticket in Wisconsin, we examined two competitive Congressional districts: one where a Democratic won and one where a Republican prevailed. Wisconsin’s 3rd Congressional District covers most of southwest Wisconsin and includes Eau Claire, La Cross, Stevens Point, and the Wisconsin portion of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area. Democratic incumbent Ron Kind, who recently announced his retirement from Congress, overperformed President Biden in this district by 4 points. In Table 3, we show that Kind did better than Biden among voters of color by 5 points, 7 points better with white college-educated voters, and 2 points better with white non-college voters.

In contrast, President Biden overperformed House Democratic challenger Ryan Polack in the 1st Congressional District, which covers southeast Wisconsin and includes Kenosha, Racine, and Walworth counties. Polack underperformed Biden by 3 points with voters of color, 2 points with white college-educated voters, and 6 points with white non-college-educated voters.

Table 3: Democratic Support in Wisconsin Key Congressional Districts and Statewide

| District | Demographic | 2020 Pres | 2020 House | Difference Pres & House |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Voters of Color | 62% | 59% | -3.1% |

| 3 | Voters of Color | 60% | 65% | +5.4% |

| Statewide | Voters of Color | 72% | 71% | -0.2% |

| 1 | White College | 52% | 50% | -1.8% |

| 3 | White College | 61% | 68% | +7.1% |

| Statewide | White College | 61% | 62% | +0.7% |

| 1 | White Non-College | 38% | 32% | -6.4% |

| 3 | White Non-College | 41% | 43% | +2.3% |

| Statewide | White Non-College | 40% | 37% | -3.2% |

This case study shows that in Wisconsin congressional districts where Joe Biden underperformed the House Democrat, it was due to weakness with all types of voters, but especially white voters with a college degree, as was the case in the 3rd Congressional District. Conversely, when President Biden overperformed the Democratic candidate, as he did in the 1st Congressional District, he did so with all groups but especially with white voters without a college degree. We are not able to speculate as to the cause of these dynamics. CD 1 and CD 3 have different political histories and demographic profiles and our data do not allow us to speak to qualitative aspects of the campaigns , including incumbency, campaign advertising, or the national political environment. However, these demographic differences are important for considering which voters might be the most likely to ticket-split in down-ballot races.

Making sense of the electorate

What Happened™ Catalist © LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Proprietary data and analysis not for reproduction or republication.

Catalist’s actual providing of products and services shall be pursuant to the terms and conditions of a mutually executed Catalist Data License and Services Agreement.